girls interrupted & foucauldian frameworks

How a close reading of a painting makes all the difference between the 1993 memoir Girl, Interrupted and the 1999 film it inspired

Today’s close reading examines the last chapter of Susanna Kaysen’s 1993 memoir, Girl, Interrupted. As a content warning, please be aware that this essay briefly references Kaysen’s suicide attempt.

I’ve been thinking about Kaysen’s memoir for a long time. I first read it in 2007, with a literature professor who introduced me to ways of thinking and reading that have changed my life ever since. I’m really excited to share today’s essay, which is really a kind of culmination of 16 years of reading and thinking about this story.

“Interrupted at her music: as my life had been, interrupted in the music of being seventeen, as her life had been, snatched and fixed on canvas: one moment made to stand still and to stand for all the other moments, whatever they would be or might have been. What life can recover from that?”

-Susanna Kaysen

Before you start reading the essay below, take a moment to look at this painting. To perform a small, quiet close reading of this work of art before reading about what Kaysen, the film, and I each have to say about it.

The thing is: you can read this painting just like you’d closely read a passage from a book. Sit with it, look at it, and let yourself wonder about it. Sometimes, it’s really the simple art of sustaining a gaze that allows our curiosity to unfold.

(Internet scrolling rarely arrests us. This is your invitation to hold still and really look at something for a moment. Try it.)

If closely reading is scary for you, or uncomfy for any reason, ask yourself these questions while looking at the painting:

What do you think the painting is about?

What do you like about it? Not like about it?

What do you make of the title?

How does the girl’s gaze feel to you? How does it feel to be looked at by her?

What’s the general emotional response you have to looking at her? (You don’t need to know why. It’s okay to just name it.)

Wherever you landed is good.

Susanna Kaysen’s 1993 memoir, Girl, Interrupted takes its name from the Vermeer painting, pictured above. It inspired the 1999 film of the same name, starring Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie — but the chapter in which Kaysen connects the painting to her own experience is left out of that adaptation. There is actually a deleted scene1 that attempts to convey the connection, but I understand why it was left on the cutting room floor. It simply doesn’t do anything in the film version.

In the memoir, however, it makes all the difference to the story Kaysen tells. In fact, I’d argue that the omission of Kaysen’s reading of this Vermeer painting from the film is the reason the memoir and film versions end up making such drastically different arguments about healing, mental health, and girlhood.

The film ends up suggesting that Kaysen eventually leaves the psychiatric facility because she takes charge of her diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder and “heals” herself through the art of writing. The memoir suggests, in contrast, that there was no clearcut healing pathway, nor an active choice to write her way out of her pain. The memoir, then, is not the tidy result of an intentional journey out of depression (as the film would perhaps suggest). It’s, rather, an ongoing discourse of Kaysen’s own exploration of her mind and her choices.

The scene

In the scene I’m closely reading today, Kaysen compares the first time she saw the titular Vermeer painting (before she is admitted to the hospital) with the time she saw it, sixteen years later, after her stay at McLean Hospital. She begins:

“The Vermeer in the Frick is one of three, but I didn’t notice the other two the first time I went there. I was seventeen…”

She walks the halls of the museum, passing the other Vermeer paintings there: “the lady in yellow robes and the maid bringing her a letter, past the soldier with a magnificent hat…” but a pair of eyes in the next painting arrest her attention: “Her brown eyes stopped me.”

“It’s the painting from whose frame a girl looks out, ignoring her beefy music teacher, whose proprietary hand rests on a chair. The light is muted, winter light, but her face is bright. I looked into her eyes and I recoiled. She was warning me of something—she had looked up from her work to warn me. Her mouth was slightly open, as if she had just drawn a breath in order to say to me, “Don’t!”

In this earlier interaction, Kaysen reads the girl as a warning sign. She even positions the girl as having interrupted her own work to stare out at Kaysen, to catch her attention. In this reading, Kaysen is the reason for the interruption; the girl exists to capture her gaze and hold her there. Perhaps even to frighten her.

Kaysen returns, sixteen years later, with a rich, jerky boyfriend. Back at the Frick, Kaysen vaguely remembers seeing the Vermeer years before. When she stands before it again, almost two decades later, she has a wholly different experience with the girl in the frame. Her close reading of the painting drastically changes:

“She had changed a lot in sixteen years. She was no longer urgent. In fact, she was sad. She was young and distracted, and her teacher was bearing down on her, trying to get her to pay attention. But she was looking out, looking for someone who would see her.

Notice that subtle shift: from a girl who interrupts herself to find and warn Kaysen to a girl who is distracted and looking for someone to recognize her. Rather than looking out in ominous warning, the girl now appears to look out with longing.

Of course, we know that the girl has not changed; Kaysen has. That’s the lovely thing about the vague references to “she” in this scene — Kaysen is writing about Vermeer’s subject, but she may be writing about herself, too. Kaysen has changed into someone who is no longer looking the same way; she’s learned to pay attention with a wholly different gaze.

This time, she closely reads the painting so differently. This time, she starts to piece together the larger story—including the painting’s title.

This time, I read the title of the painting: Girl Interrupted at Her Music.

Interrupted at her music: as my life had been, interrupted in the music of being seventeen, as her life had been, snatched and fixed on canvas: one moment made to stand still and to stand for all the other moments, whatever they would be or might have been. What life can recover from that?

I had something to tell her now. “I see you,” I said.

This time, in yet another departure from her past interaction, Kaysen takes part in the interrupting gaze. Rather than being looked at, caught and warned, Kaysen gazes back. She even speaks directly to the girl, acknowledging the quiet work her bold gaze, out of the frame, does in creating a real identification between them. In other words: while Kaysen’s previous interaction with the painting rendered herself the true subject of the work of art, by making herself the one “looked at” by the girl, Kaysen’s more mature gaze allows the young woman of the painting to exist separate from herself, as someone to be seen. As a subject unto herself.

My boyfriend found me crying in the hallway.

“What’s the matter with you?” he asked.

“Don’t you see, she’s trying to get out,” I said, pointing at her.

He looked at the painting, he looked at me, and he said, “All you ever think about is yourself. You don’t understand anything about art.” He went off to look at a Rembrandt.

It strikes me just how wrong (and dumb) her boyfriend is, in this moment. And how cruel he is to brand her interaction with art as selfish. The irony, of course, is that it was Kaysen’s previous interaction with the painting—in which she made herself the reason for its existence—far more self-centered. This later interaction with the girl in the painting is anything but selfish; she seems, very much, to understand art.

Then, the book ends with a few more ruminating thoughts:

I’ve gone back to the Frick since then to look at her and at the two other Vermeers….

The other two are self-contained paintings. The people in them are looking at each other—the lady and her maid, the solder and his sweetheart. Seeing them is peeking at them through a hole in a wall. And the wall is made of light—that entirely credible yet unreal Vermeer light.

Light like this does not exist, but we wish it did. We wish the sun could make us young and beautiful, we wish our clothes could glisten and ripple against our skins, most of all, we wish that everyone we knew could be brightened simply by our looking at them, as are the maid with the letter and the soldier with the hat.

The girl at her music sits in another sort of light, the fitful, overcast light of life, by which we see ourselves and others only imperfectly, and seldom.”

(I’m always gobsmacked by the beauty of her prose here. I could write an entire essay on that alone.)

By interacting with art, Kaysen finds a way to articulate what she has lived through with a sense of fullness. She suggests a kind of Foucauldian culpability of the cultural system that raised her without doing so by erasing her individuality. Put another way: by close reading Vermeer’s painting, Kaysen makes the subtle argument that her mental health experiences were not something to “fix” or “change” about herself.

Viewers of the film will know that the ending of that version shows Ryder’s Kaysen deciding to take control of her life, and her depression and anxiety, by throwing herself into a dream of becoming a writer. A beautiful montage shows her journaling, gazing out the windows at her coming freedom, embracing an empowered control over her impulses—channeling her pain into art—in a way that is both encouraged and celebrated by her caretakers in the facility.

Readers of the memoir experience something quite different: Kaysen grappling with how much she recognizes the girl’s gaze in the painting: a longing to get out, a trapped-ness in a framework she didn’t create, and a wordless gaze that manages to communicate more than words can say.

Kaysen & Foucault

Let’s take things one level deeper.

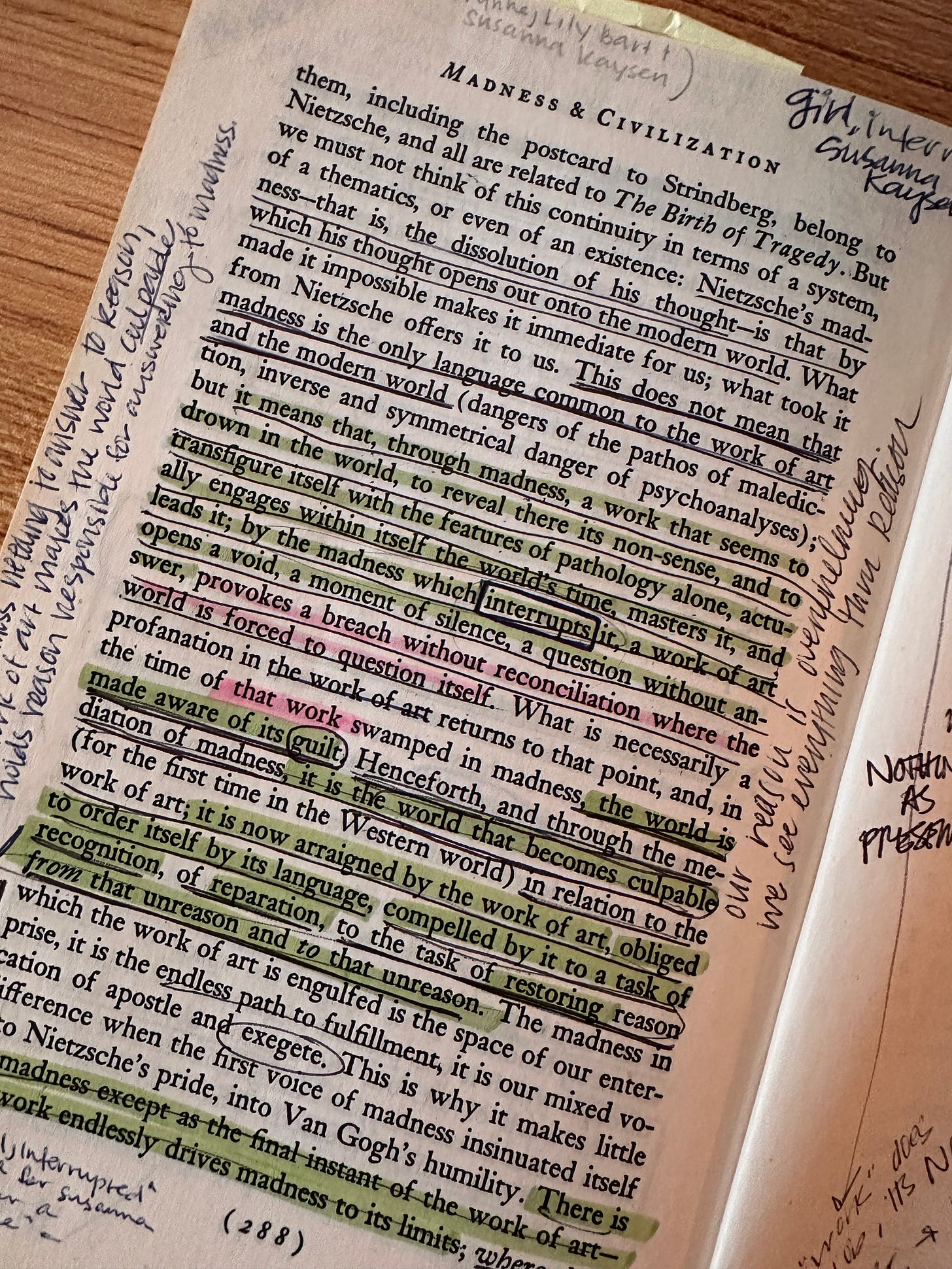

Kaysen’s engagement with Vermeer’s painting recalls a moment at the end of Michel Foucault’s 1965 history of madness: Madness and Civilization. For me, Kaysen makes Foucault’s huge claims about art and sanity understandable.

He writes in his preface that his goal is to examine that strange place “which is neither the history of knowledge, nor history itself….A realm, no doubt, where what is in question is the limits rather than the identity of a culture.”2

I think of Kaysen’s memoir as residing in that realm: a place where what is at stake is not necessarily a better understanding of the 1960s cultural realities that led to her being so easily signed into a hospital for troubled teen girls, against her will. Though we certainly do gain that. I read Girl, Interrupted as a memoir about questioning limits: of what’s permissible, of what is “sane” and “not sane,” of where the line gets drawn between real and not real, good and bad.

Indeed, a scene from the film with Kaysen’s psychiatrist, Dr. Wick, takes up this question of boundaries beautifully as Susanna and her doctor discuss the word “ambivalent.” In this scene, we see the film (again) playing with the idea of “either/or” questions that turn Kaysen’s diagnosis into “the choice of her life.”

The memoir, especially in a Foucauldian reading, suggests something else in Kaysen’s reading of Vermeer’s painting. Not an easy “either/or” framework, but a framework-busting interruption that questions the way we create meaning and establish truths.

Foucault writes:

By the madness which interrupts it, a work of art opens a void, a moment of silence, provokes a breach without reconciliation where the world is forced to question itself.

I read Kaysen’s interaction with Vermeer as this moment of interruption. For what Kaysen does is allow herself that “moment of silence” with Vermeer’s work, and in that moment, finds herself changed. The girl seems to have transformed from urgent to sad, from a warning to being “snatched and fixed on canvas,” where one moment in her life becomes the only one we know about her or care to look at.

Kaysen, by invoking the power of that rare and unreal Vermeer light suggests that we might learn to look at the world—and the people in it, their own “snatched and fixed” moments—with a little more grace, a little more patience.

What is a memoir if not an author’s intentional, careful work to “snatch and fix” their life story in writing? To curate moments that matter and leave the rest on the cutting room floor?

Kaysen subtly undoes the fixedness of such a framework by including this final chapter in her book. By that, I mean that she challenges the meaning of her stay in the hospital, of the time her life was interrupted, as the moral or the lesson. She decenters that experience as the sum “why” of her existence.

Foucault helps me see that her invocation of art invites readers, and maybe also herself, to flip the power dynamic of the story—or to question it entirely. Perhaps it was not Kaysen’s depression, her diagnosis, or her actions that are the whole picture. Perhaps if we learn to see her under that “fitful overcast light of life,” we might come to a fuller, more true understanding of what her memoir sets out to tell us.

By gazing out from her own story in the final chapter, Kaysen suggests that art—and interacting with it, having a genuine response to it, letting it look right into our souls, and daring to look back—can change our lives. Or maybe just change the way we “snatch and fix” the moments of our life in story. Can thereby, then, remind us that moments of rupture are not the whole story, even if they are where an incredible story might emerge.

Indeed, it’s in that Foucauldian moment of interruption where “the girl at her music sits in another sort of light, the fitful, overcast light of life, by which we see ourselves and others only imperfectly, and seldom.” The rarity of it, for Kaysen, makes it all the more meaningful. As she puts it, “Vermeers, after all, are hard to come by.”

Hey, you made it to the end! I want to know: Did you closely read the painting before, during, or after you read today’s essay? If so, please tell me your thoughts about it in the comments.

Click the link and fast-forward to minute 10:48 - 11:59 for the scene in the museum.

If you’re reading along, this quote comes from page xi in the preface.

Haley, when I saw you commented on my post I immediately went to your substack and searched for this post. I have read this twice now. so enlightening! I actually didn’t mind much about the difference about the book and movie because, uhm, it was just a movie. But after reading this I realized how important it was to show the painting scene in the movie although they’d have to reinvent the whole story line haha.

That part about the light. I always found it so beautiful but I couldn’t grasp it as much as I want to in my head so thanks for articulating what I was thinking of!

wow I'm working on girlhood and the gaze and this was so so interesting !!