"he doesn't even know what I'm feeling"

Week 6 | Analyzing Book 4 of The Custom of the Country

Welcome to the Closely Reading book club: a space where we closely read classic literature together and discuss assigned chapters each week. We’re currently wrapping up our read of Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country—you’re welcome to join! Here is the introductory post, if you’re just tuning in.

Content warning: Please be aware that today’s guide includes allusions to a character’s suicide in the novel.

Thank you for your patience as I get each week’s guide out to you! As you may know, these read-a-longs are my passion project, and not my full-time job. (My dream! Someday!) Now: onto the guide…

Book 4 flies by…

Ralph is back in the center, after we learn of Undine’s plans to have her marriage annulled so she can marry the Frenchman.

And just as Ralph starts to finally find himself — his happiness, love, and peace — Undine makes a showy announcement in the papers that she’s all-but secured her annulment and wants Paul as part of the deal.

“That the reckoning between himself and Undine should be settled in dollars and cents seemed the last bitterest satire on his dreams: he felt himself miserably diminished by the smallness of what had filled his world.”

(It struck me as deeply meaningful that it was novel writing and finding his literal voice again that helped Ralph start to heal…)

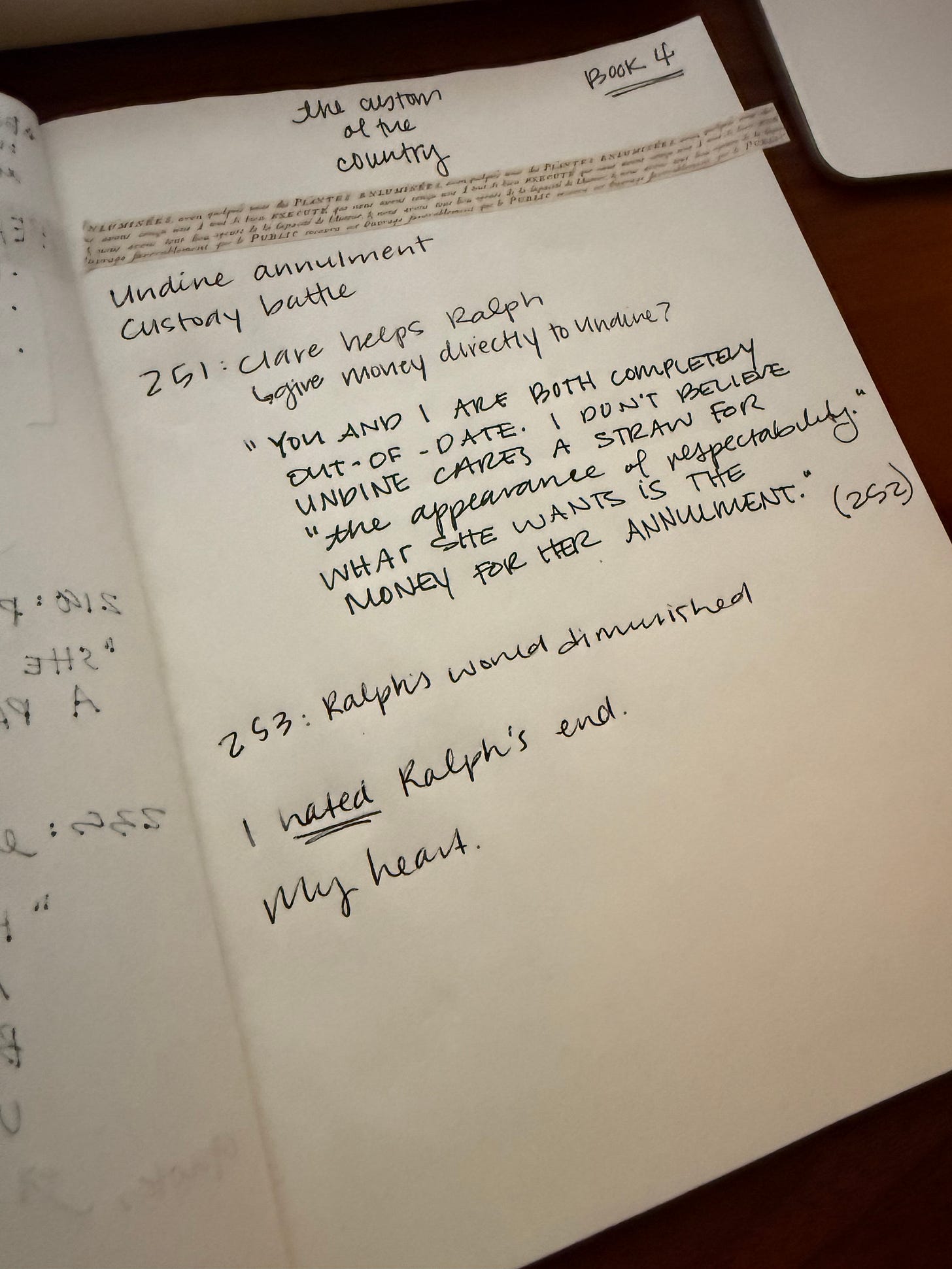

Just as my heart started pounding, I realized along with Clare Van Degen that I was also “completely out-of-date” in thinking Undine actually wanted her son. Elmer Moffatt had plainly spelled out the plan for her at the end of Book 3; and now she’s simply executing on another shrewd business deal:

“I don’t believe Undine cares a straw for ‘the appearance of respectability,’” Clare Van Degen plainly states: “What she wants is the money for her annulment.”

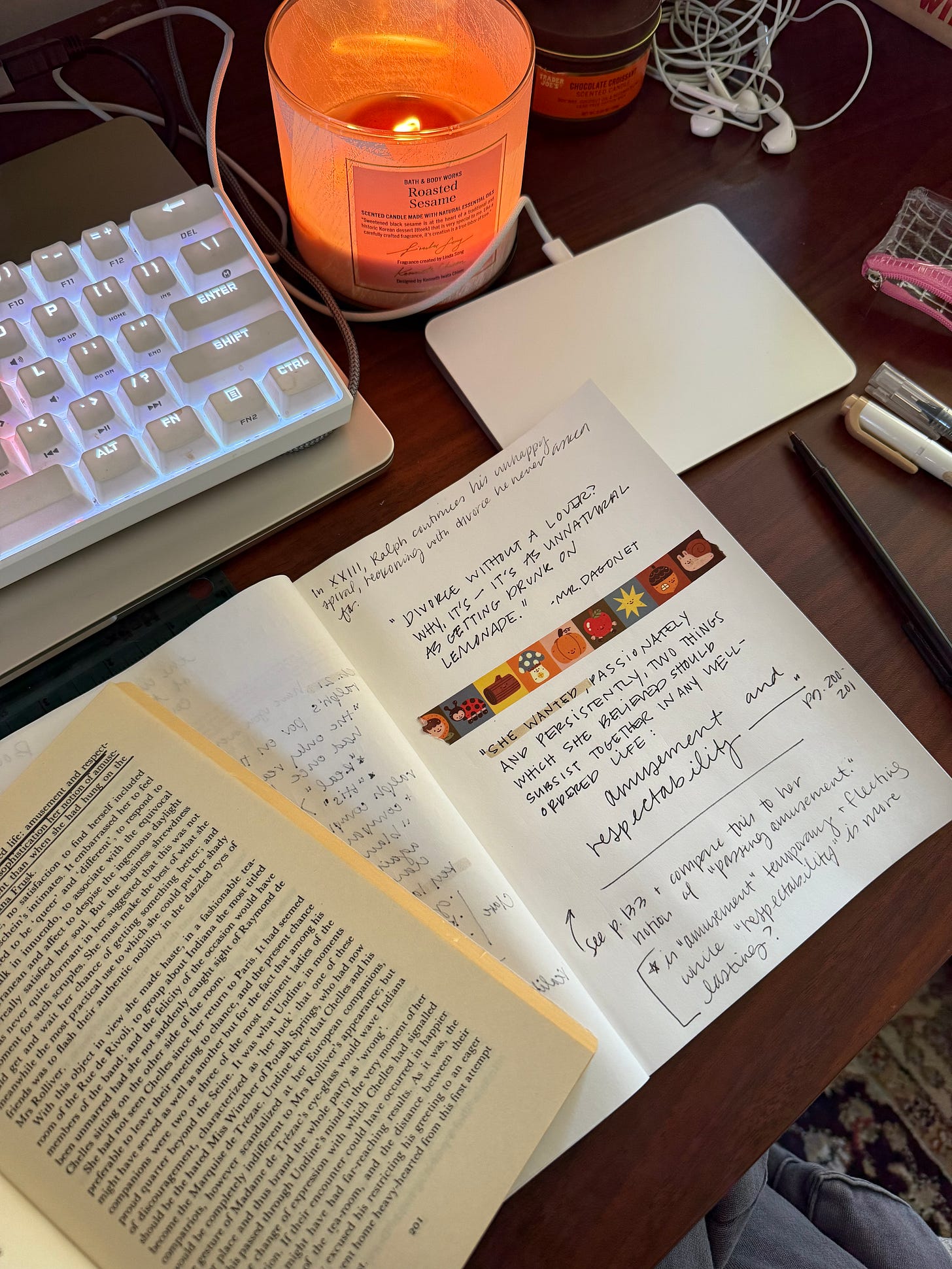

When the novel first mentioned, in Book 3, that Undine has deluded herself into believing she wants only “amusement and respectability,” I laughed into the margins. No she doesn’t! She doesn’t care at all about anything but her own desires being endlessly met. It’s not even “amusement,” and it’s certainly nothing to do with “respectability.”

All Undine wants is money. More of it, always.

And thus we have the shape of the conflict in this, the fourth act of this roller coaster of a novel.

Undine’s next (final?) attempt to rise from the ashes, like some evil-tuned Phoenix, is to wring the Dagonet family dry of all their money and to take Paul away if they refuse her.

(It seems so strange and naive to me that Undine seems always to believe that there’s an infinite amount of money, tucked away, ready for her to use up. This feels like a strange and untested fantasy she has about the Old New York she idealizes: she thinks of it as this unlimited place for potential, growth, and taking. She never once hits a real limit that teaches her to stop before someone gets hurt.)

And though they do not refuse her, the revelations of Elmer Moffatt to Ralph Marvell result in one of the more tragic shocks I’ve ever experienced in a novel.

Can I tell you: when we first started this novel, I thought back to the first and only time I’d read it, about 12 years ago, during my MA program. I did not remember the ending at all, only that Undine was terrible.

I cried and cried as we reached the final paragraph of Book 4, where Ralph takes his life after learning what a liar Undine has been all along: she knew he’d never marry a divorced woman; Elmer sat in their dining room; she machinated deals for Elmer at her father’s and Ralph’s expense; and now, she was threatening to take Paul away, for nothing more than additional income to spend on herself.

He’d been so ill when she first deserted him; maybe I should’ve seen it coming. But I didn’t.

The language of the novel, when it comes to Ralph, has been so up and down — just like Undine’s social fluctuations. He’s been overjoyed and in love; he’s been disillusioned and sick; he’s been a devoted father and an eager friend; he’s been broken and beaten down by Undine’s sick games.

My heart broke at his final thought: “My wife…this will make it all right for her.”

Undine thrusts herself into the center of his life, even after she has deserted him, and so there is no room for himself, for Clare, or even for Paul in his own mind and heart. He ruins himself to meet her demands. She consumes everything and, in the end, consumes Ralph.

I wish they’d never met.

Ralph’s ending struck me as heartbreakingly reminiscent of Lily Bart’s, and I’ll be thinking about the connections between the two for a very long time.

Contrasting Clare and Undine, again

The profound comparisons between Clare and Undine were on display again in this Book, as Clare works hard (and reveals her secret stash of savings) to help Ralph while Undine attempts to wreck him once again.

“I’ve been hoarding up my scrap of an income for years, thinking that some day I’d find I couldn’t stand this any longer…”

Oh, poor Clare. The small income she’s put away for herself, should she need it in the event she decided to divorce Peter will now fund Ralph’s custody battle for Paul. What a cruel, clever twist.

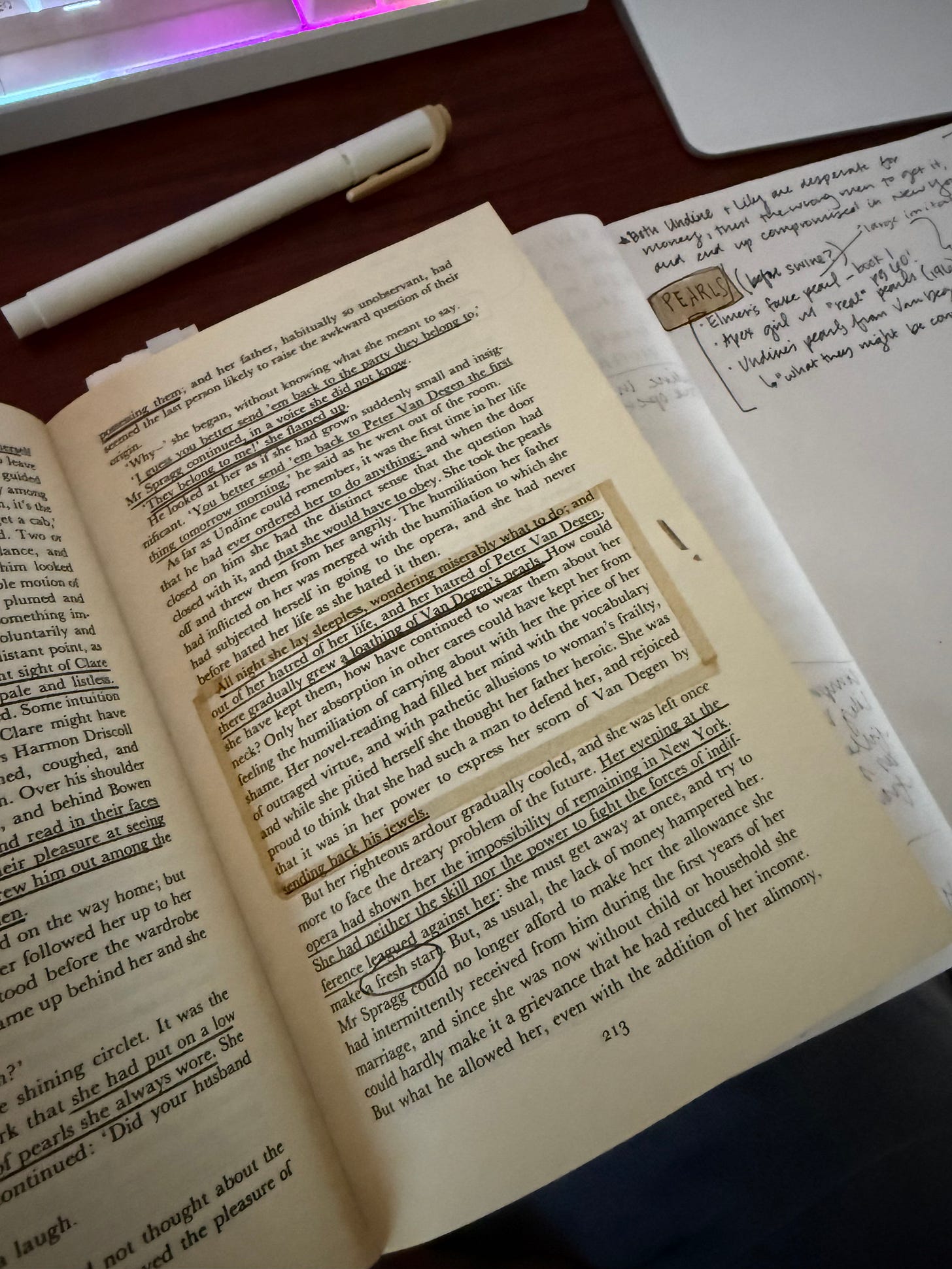

This twist pulled me back to thinking about the way Van Degen unwittingly funded Undine’s next scheme with the expensive pearls he bought her during their affair.

As you can see in my notes above, I flew back to the first time Elmer confronts Undine in Book 1, where he wears a “large imitation pearl.” Then, to the page in Book 3, where Undine loathes the “very real” pearls of the Apex girl she has long tried to out-run with her social rise. Finally, I came to the page (213 in my edition) where Undine experiences “a loathing of Van Degen’s pearls.”

All along, pearls have played a wildly symbolic role in the novel as cues to Undine’s “rise” arcs and as harbingers of schemes to come. Almost like the color red in a Shyamalan movie, pearls in The Custom of the Country cue us, as readers, to know that some new bitter social play is about to take place.

It’s Mrs. Heeny, that same masseuse and social massager of opportunity for Undine, who helps her realize the pearls can be her escape into another chance at social reign: the necklace is worth so much money that Undine can live on it in Paris long enough to secure Chelles for her next marriage.

(We can consider this her fourth marriage, can’t we? She was engaged to Millard Binch. She divorced Elmer. She was almost-married to Peter Van Degen. She left Ralph, and now she’s got the Pope calling for an annulment. Holy moly. She’s going through husbands like a maniac.)

And now, in a twist of Whartonian irony, Clare Van Degen will use her savings (the same she has quietly tucked away during her marriage to Peter) to undo Undine’s scheme and buy Paul back for Ralph. It was all tied to these pearls.

Elmer as the large, phony pearl in the opera box that announced his out-of-placeness but his clear willingness to “fake it ‘til he could make it.”

The “real pearls” that signal to Undine that even clumsy girls from Apex can be successful in winning over rich men in New York.

The expensive necklace from Van Degen that opens the door to Undine’s annulment…

It’s a wickedly smart set-up, isn’t it?

Add into the mix that Rolliver and Moffatt are at the heart of the business deal into which Ralph, his family, and Clare dump their $50,000 investment (equivalent to at least $1.7 million in today’s dollars…)

The smallness of this society is shocking, isn’t it? Even when Old New York fails to keep its tight boundaries, even with new young Apex wives and the nouveau-riche on the scene, the world of New York remains very, very small.

It’s downright dastardly.

And so claustrophobic — so endlessly traumatizing for people like Ralph — that it ends up, well, breaking them.

I’m struggling to read this as Social Darwinism: as a moment of “survival of the fittest,” where terrible Undine is “fitter” and therefore outlives Ralph in the jungles of New York society. There are key complications to this narrative of American Naturalism:

Undine has not survived in New York society; she’s essentially self-exiled herself to Paris where, having burned through the cash from the necklace, she relies on the income from basically blackmailing Ralph to sustain her new marriage.

Ralph is not unfit. In fact, he’s a product of the Old New York system that has produced him and his beloved, Clare. And yet, the novel does make some layer of commentary about the “death” of Old New York — and all its rituals and customs — with Ralph’s death, doesn’t it?

What of Paul, their “offspring” (to put it in Darwinian terms)? The novel has made mention of how alike he is to his father; Laura Fairford even wishes for him to have more “Spragg” in him. Will the Spragg in the punnet square make Paul more “fit” for modern society than the Dagonet and Marvell strains of DNA did?

It’s time to finish Book 5

Get all caught up and read through Books 4 and 5 this week, if you haven’t yet!

(Many of you have let me know you finished early, and I don’t blame you!)

Our original schedule has you set to finish the novel by October 26, so you can start on the academic readings.

If you’ve fallen behind, this novel is definitely readable in a single week (or, as some of you have told me, in a single sitting!) If you’re just starting, you have plenty of time to read + join us for the deeper academic conversation, starting October 27.

I’m so excited to hear your thoughts on the next sections. I’m all caught up, and was able to get the next guides done on time, so we’re back on schedule.

Keep reading! Let’s finish the novel strong, and then we can get into the assigned academic essays.

Thoughts for next week

If you’re going to be reading the academic essays with me, I recommend getting them printed (if you’re paying for JSTOR premium) or getting them pulled up on your computer this week, so you can figure out the best way to read + annotate digitally.

Once you’ve finished the novel, you’re good to start reading the assigned academic essays. If you’d like to wait for a bit of guidance from me, it’s coming with the final novel guide next week (for Book 5/end of novel).

Done with the novel? Read this piece by Jia Tolentino in The New Yorker.

I’ll be coaching you through the reading experience of these articles, and giving you expert tips for tracking academic arguments! :) I’m SO EXCITED to get to this part!

During the week of Monday, October 27

Finish the novel + Read the Sheila Liming article (linked below)

During the week of Monday, November 3

Read the Margaret Toth & Regina Martin articles (linked below)

Available on JSTOR:

“Shaping Modern Bodies: Edith Wharton on Weight, Dieting, And Visual Media” by Margaret Toth

“The Drama of Gender and Genre in Edith Wharton’s Realism” by Regina Martin

Remember: If you want to be able to print these essays, you’ll need to pay for the JSTOR monthly membership (I believe it’s about $20 USD). Consider making your own textbook! If you’re okay to read digitally and take notes manually, you can access these articles with the free JSTOR membership.

Select “Register” to create a free account

Once you’ve created your account, you can upgrade if you’d like to be able to print 10 articles per month!

More to read

Want to read more modeled analysis to get the hang of things?

—> Closely reading the first sentence of The Age of Innocence

Want more reading ideas?

—> Browse all my Edith Wharton reading recommendations

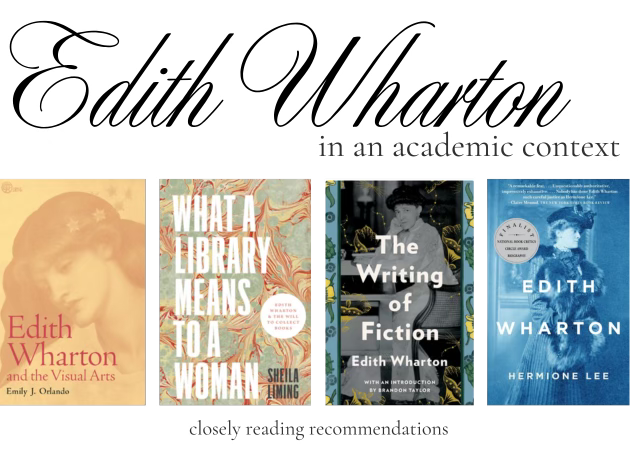

Edith Wharton and the Visual Arts by Emily J. Orlando (one of the best academic books I’ve ever read!)

What a Library Means to a Woman by Sheila Liming (I love this book)

The Writing of Fiction by Edith Wharton (her nonfiction about writing)

Edith Wharton by Hermione Lee (an outstanding biography)

You can watch Lee’s hour-long discussion of Wharton here

Consider a paid subscription

Choose any of the options below. Paid subs get extra reading resources, Etsy shop discounts, and more!

🥐 $15 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $15. Available to all readers, all the time.

This rate helps me keep our readings open to all readers!💌 $25 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $25. Available to all readers, all the time.

This rate helps me fund creative projects and reading materials.📚 $50 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $50. Available to all readers, all the time.

This rate helps me purchase academic books in my research area.☕️ Buy me a coffee (or a new book!)

Make a simple, one-time donation to Closely Reading

This income is my go-to fund for coffee shop work days!

I was devastated when Ralph killed himself but not surprised - it was foreshadowed throughout Book 4, especially with the narrative buildup of Ralph (and Clare) investing in the shady Apex scheme and Moffat sleazily putting him off about getting a timely return on the investment. The fact that Ralph needed that money to keep custody of his son with his family made me hate Undine even more. (Toward the beginning if Book 5, she is described as explicitly thinking of Paul as a good “acquisition.”)

Tracking the role of the pearls is really intriguing as a narrative device, Haley, especially when I think about what pearls are: the secretions of a mollusk around an irritant like sand - that is, something beautiful harvested from pain. And then there’s Undine the nacreous, lacquered sea creature herself - and even (possibly) hints of Gilded Age excess like Oysters Rockefeller. Wharton the sharp-eyed social observer and author layers the references on in her brilliantly concise descriptions - word pearls, so to speak, that also hurt.

Ralph, no!

"He seemed to be stumbling about in his inherited prejudices like a modern man in mediaeval armour…and the whole archaic structure of his rites and sanctions tumbled down about him."

Such a beautiful resonant quote. It got me thinking how it applies to many characters in my favorite books. Whether it is psychological trauma, displacement due to natural disasters, societal changes or times of war, we invest in a character and get to follow as they navigate what happens when their "structure of rites and sanctions" is destroyed and when their "inherited prejudices" are laid bare. We get to explore how they choose to face these realities and consider how we would act in their scenarios. I hope I would be stronger than Ralph, but of course I always want to believe I'll be the one who can make the heroic choices. I'm glad my collected cast of literary characters with their cautionary or inspiring stories now live with me. With each great book I read I learn again how true it is that story has always been the way that humans pass wisdom to succeeding generations. I can never be sure what an author like Wharton intended to say in her creation, I only know what I've extracted from it. I guess that's why reading great books at different times leads us to glean different understandings.