"a monstrously perfect result of the system"

Week 4 | Analyzing Book 2 of The Custom of the Country

Welcome to the Closely Reading book club: a space where we closely read classic literature together and discuss assigned chapters each week. We’re currently reading Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country—you’re welcome to join us any time. Here is the introductory post, if you’re just tuning in.

Thank you for your patience as I took an extra week to get the Book 2 guide out to you! As you may know, these read-a-longs are my passion project, and not my full-time job. (My dream! Someday!) Now: onto the guide!

Welcome to week 4

After so much motion in Book 1, Book 2 opens with Ralph “stretched on his back in the grass,” as he lay “prostrate beneath the sun.”

We can compare this vision of leisure and relaxation to Undine — who seems serene, but fidgets with “the slightly constrained air of a person unused to sylvan abandonments.”

I had to look up “sylvan” in my dictionary; it’s a word associated with wooded areas and the pastoral. In other words, in this moment, Undine acts like a person who is not accustomed to the countryside, or the pleasures of leisure. Later, we learn that her “pliancy and variety were imitative, rather than spontaneous,” and this compounds the image in my head of Undine as a rather “inelastic” person. She is constantly performing and imitating someone she deems more classy, important or knowing than herself; this makes her anxious and fidgeting.

Out in the countryside, honeymooning with Ralph, Book 2 traces Undine’s perpetual fidgeting socially: she will not ever be at rest until she has achieved that amorphous status she so tirelessly seeks. Undine is restless, even after having married up, established a name for herself, and even having a son in a well-established Old New York clan.

Nothing is enough for Undine.

Rapid developments unfold

In this week’s chapters, so much happened!

Undine and Ralph honeymoon in the off season: it’s too hot, they burn through their funding, and Undine is pissed there isn’t a big crowd around to imitate.

Undine just really isn’t that into Ralph: her muted responses, “resigned” attitude and spoilt dismissals of him (and their poor little son later in the chapters) make it obvious that her heart, mind, and energy are all going elsewhere.

Undine and Ralph have a son; Undine couldn’t care less about him. This is a woman who resents every facet of motherhood: pregnancy (her dresses won’t fit!), rearing (she has more important things to do!), and loving (she is really just way too narcissistic to love anyone but herself…)

3 years after the honeymoon, Undine sits for Claude Washingham Popple — and her portrait draws a huge crowd, including that elusive Peter Van Degen, who flatters her and takes her for, ahem, a ride.

She misses Paul’s birthday party; we learn it’s far from the first time she has spoiled plans and lied about why.

Undine is “a monstrously perfect result of the system: the completest proof of its triumph” and ohhhhh do we need to talk about this or what?

She starts accepting money from Van Degen and I could not help but remember what happened when Lily Bart accepted money from Gus Trenor in The House of Mirth. And yet…I can’t seem to imagine Undine will experience the same consequences Lily did. This has thrown me into deep introspection in which I am still very tangled in my thoughts; yes, I cried for Lily. AGAIN.

Chapter 16 was amazing, and it teaches Undine that “what she wanted was not a hand-to-mouth existence of precarious intrigue: to one with her gifts the privileges of life should come openly.” In other words: Undine does not want to subsist on the finances earned from married men who send her money in exchange for secrecy and fantasies. She wants, once again, that elusive “something more.” She wants her “gifts” (beauty? beguiling charm? imitation?) to earn her long-term success; not the “immediate success” she watches other women fail to sustain.

Undine appeals to her father on terms of class: she is unhappy at home, but moreso she is unhappy that she — and her father — are expected to pay for Ralph’s lifestyle while his family shames him for working. (The way Undine cast clarity on these “customs” was staggeringly beautiful to me; she ripped those honored old traditions to shreds and I loved every second of it! Yes, she did it for her own gain, but hasn’t the system trained her to do so? Is she wrong?)

Undine’s wonderful foil, Elmer Moffatt, makes another appearance in her father’s office, and then Undine introduces him to Ralph…and a business deal starts brewing that casts Ralph as a “useful intermediary.”

I call him a foil because he’s always cast in a stranger and less forgiving light than Undine; he’s like her male twin. An inverse who isn’t as capable, as she is, at imitation and charm. He lays bare his mocking of the very society that mocks and keeps him out, even as he keeps finding ways in. He and Undine are on parallel paths, it seems.

Undine falls under the “verge of a nervous attack” and Ralph worries not about her health, but the costs of a medical episode.

Undine’s father encourages Ralph to send her to Europe.

My jaw dropped! Mr. Spragg knows what Undine means to do in Paris — she intends to replace Ralph. And while with Undine, he rejected the idea, he’s now encouraging Ralph to send her. Is it because he saw Ralph do business with Moffatt!?

Undine learns that Indiana Frusk has risen in society: she is replacing Rolliver’s previous wife (exactly what Undine wants to do with Van Degen). These Apex girls don’t mess around, do they?

In Paris, Undine resents Ralph, spends all their money, and gets her first “real glimpse into the art of living.” She’s ready to leave that life behind…and right on schedule, we’re due to enter a new epoch of her life in our next reading, Book 3.

Who will Undine woo next? Will she marry Chelle? Will she continue to wind Peter Van Degen around her pinky? Is anyone safe in her orbit?!

“Undine was not consciously acting a part: this new phase was as natural to her as the other. In the joy of her gratified desires she wanted to make everybody about her happy. If only everyone would do as she wished she would never be unreasonable.”

“a monstrously perfect result of the system: the completest proof of its triumph”

We’ve simply got to talk about the fact that Undine is a “perfect result” of the system in which she has been raised.

Wharton is one of my favorite “systems thinkers,” and by that, I mean she’s one of the best authors I’ve ever read when it comes to connecting societies with individuals. Her novels stage Old New York against the nouveau riche, and yet they do so not through the systems themselves but through the individual dramas of the people who exist within these settings.

When we read that Undine is the “monstrously perfect result of the system,” we’re not just learning something about Undine. We’re learning about the conditions — familial, social, economic, emotional — that have raised Undine. Not just her parents, but her entire ecosystem. (Her parents are, after all, a part of the system, themselves).

In Paris, Bowen watches the Van Degen dinner with Undine at the Nouveau Luxe (what a modern setting!) and sighs at all the implications of Undine’s behavior in Paris, away from her family. Bowen “felt the pang of the sociologist over the individual havoc wrought by every social readjustment: it had so long been clear to him that poor Ralph was a survival, and destined, as such, to go down in any conflict with the rising forces.”

This is smart, tight foreshadowing: Ralph is a remnant of an old system, one in “havoc” due to the “individual” actions that force the larger system to “readjust.” This is not a simple black-and-white manner: there is no system that solely acts on individuals; there are no individuals that exist without a system around them. These two forces are inherently intertwined.

And it matters that Wharton draws these connections, between the individual and the society, between the “survival” and the “rising forces,” because it allows us to tangle with questions of culpability, responsibility, and authority. By this, I mean it allows us to ask questions like:

Who is responsible for Undine’s performativity? Her skills of imitation? Did she learn them to survive? (This cracks open questions of Social Darwinism, a literary movement of which Wharton was a keen leader.)

What is the purpose of marriage? Of divorce?

Who, or what, is responsible for Undine’s beliefs about marriage? Where do those beliefs come from? What shapes them? What influences them?

Who has authority in this system?

Who gains authority? Who loses it? How is it held? How is it lost?

We can ask ourselves again: at the end of Book 2, what will Undine want now?

How has the system or the society shifted in Undine’s mind? How does her individual success or failure within that system reflect her understanding of the system?

In the final chapter of Book 2, Undine sits in “her recovered Paris,” where “it seemed so perfect an answer to all her wants!”

Is she going to finally achieve her long-awaited dreams? Will anything ever sate the gaping maw of Undine’s desire?

Thoughts for next week

Now that we’re solidly into the story, I want to hear from you in the comments this week:

What themes are you tracking? Are they the same themes you noticed in the first chapters? What themes have evolved or become new for you in the last week of reading?

What do you think of Undine? Do you like her? Hate her? Admire her? Fear her?

Cards on table: I love her. I don’t love her choices or her actions; I love here existing as a character who gets a whole book about her. She demands an audience, and she keeps getting one. Wharton gives her one by writing the novel. And so far, I don’t get the sense that our narrator dislikes her. Fascinating. Because Undine is pretty easy to dislike.

Keep reading!

Read Book 3 by mid-week (when the next guide drops!) then complete Book 4 by next Monday. We’re moving fast!

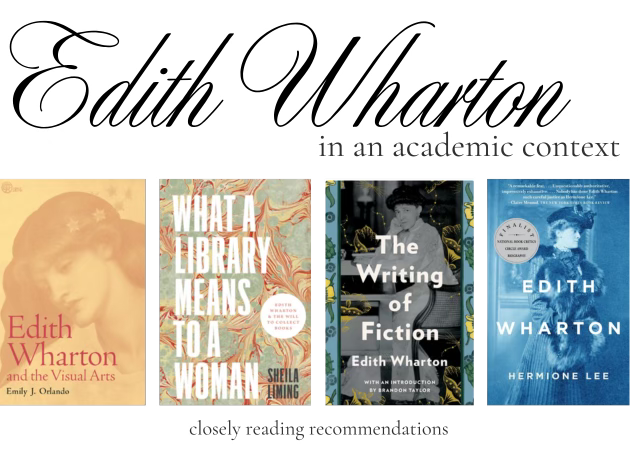

Want to read more modeled analysis to get the hang of things?

—> Closely reading the first sentence of The Age of Innocence

Want more reading ideas?

—> Browse all my Edith Wharton reading recommendations

Edith Wharton and the Visual Arts by Emily J. Orlando (one of the best academic books I’ve ever read!)

What a Library Means to a Woman by Sheila Liming (I love this book)

The Writing of Fiction by Edith Wharton (her nonfiction about writing)

Edith Wharton by Hermione Lee (an outstanding biography)

You can watch Lee’s hour-long discussion of Wharton here

Consider a paid subscription

Choose any of the options below. Paid subs get extra reading resources, Etsy shop discounts, and more!

🥐 $15 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $15. Available to all readers, all the time.

This rate helps me keep our readings open to all readers!💌 $25 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $25. Available to all readers, all the time.

This rate helps me fund creative projects and reading materials.📚 $50 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $50. Available to all readers, all the time.

This rate helps me purchase academic books in my research area.☕️ Buy me a coffee (or a new book!)

Make a simple, one-time donation to Closely Reading

This income is my go-to fund for coffee shop work days!

Haley, did you queue these two masterpieces up this way on purpose? Undine and Ralph Marvel echo and amplify Rosamond and Lydgate.

Ralph realizes that his wife's disregard for money comes with "blind confidence that it will somehow be provided". It was Rosamond "who never thought of money except as something necessary which other people would always provide."

Lydgate and Ralph each fall for a beautiful girl that they envision as their internal image of ideal womanhood. Rosamond "would reverence her husband’s mind after the fashion of an accomplished mermaid, using her comb and looking-glass and singing her song for the relaxation of his adored wisdom alone”

Ralph sees Undine "like a lovely rock-bound Andromeda, with the devouring monster Society careering up to make a mouthful of her; and himself whirling down on his winged horse...to snatch her up, and whirl her back into the blue"

When reality intervenes, both men scramble to maintain the illusion. Ralph seeks to "to guard himself from the risk of judging where he still adored”. Lydgate decides that "She will never love me much,” is easier to bear than the fear, “I shall love her no more.”

I can't yet even begin to dissect how even now society uses and reinforces fantasy to motivate and disappoint us when navigating the reality of relationships. It's too depressing to end on Ralph's conclusion (with Wharton using yet more water imagery) that "they were fellow-victims in the noyade of marriage, but if they ceased to struggle perhaps the drowning would be easier for both." That these authors can share truth that resonates a century or more later is nothing short of miraculous. I am so glad to be reading them here.

As I consider Undine's progress in *The Custom of the Country*, I’ve been thinking about Diane Keaton and what she represented for me as a bohemian woman who lives her own life. I'm very sad about her death, something I'd never feel for Undine Spragg's passing (or her celebrity equivalent: a Kardashian? Zsa-Zsa Gabor??). I grew up in the 1970s and ‘80s, and Keaton’s Annie Hall, with her male tie and vest and funny hat, and most especially, her funny sweetness, made her an icon for me. I think we’re all shaped by our own lives and cultural times, which is likely why I find Undine to be so repellant. I have plenty of biases as a feminist, so for me, a female character like Undine could never be a hero — but neither is Elmer Moffat, her male shadow twin. Give me Annie Hall rather than a female version of Donald Trump any day.

In answer to Haley's question, I hate Undine as a person. She’s awful to family members, knocking them aside like gnats she barely thinks about (at one point with the Spraggs, the narrator describes Undine never being moved to think of her own parents as “interesting” and is amazed anyone else would find them so). She’s a narcissistic performer who sparkles for hangers-on and admirers but turns ugly when anyone questions her motives. In many ways, she’s a great character, in that she has my attention, but I feel a little itchy reading a whole book about her.

But I’m enjoying the book, too, and find it to be a very fast read (while traveling, I couldn’t put it down, and I’m now up to Book V). I began reading it wondering if it was possible to care about a main character with no inner life. That’s a theme I’ve been tracking, along with the comparisons between the many levels of American and European society. At this point (trying to avoid spoilers), I’ve answered my own question: I find myself repulsed by Undine’s inner void. I guess I do care, but in a judgmental negative way, which also doesn’t feel comfortable to me as a reader. This is a satire, and I think Wharton the author appreciates Undine’s ruthlessness and ability to get what she wants compared with passive, moony-eyed Ralph. Yet I still feel something positive for Ralph. At the very least, I feel sorry for him.