Hello all and happy Sunday!

Firstly: a sunny-warm welcome to the many new subscribers who have joined us for The Age of Innocence read-a-long! You can review all the details for the reading group right here.

For Wednesday, May 8, all you need to do is obtain your copy of the novel and read chapter 1. (It’s just a few pages!)

Sentence-level close readings

As we embark on a close reading together — and as we all dive into our summer reading lists at large — I thought it’d be fun to share one of my favorite ways to closely read: sentence analysis. So today’s short essay is a departure from the typical close readings and is more of a miniature writing or annotation lesson.

It builds on a previous annotation lesson I’ve shared: a mini-lesson on how to closely read a paragraph in a novel to help you identify themes or patterns within that paragraph that you can map to your reading of the book-at-large.

Today, we’re pushing those close reading skills even deeper with an activity that helps you map (almost) every word in a single sentence from your current fictional read and use your observations to reveal the building blocks of the story you’re reading. This activity can be repeated as many times as needed, on as many sentences as you wish, to help you build out a deep reading of the words that make up the story you are reading, and help you develop your point-of-view on why those words matter.

(Note: this activity does not often work as well for nonfiction, though it is quite useful, with slight adaptations, for philosophical and critical texts! This activity may also be difficult to apply to light or pop fiction where the craft is less important than the plot details — however, even in these cases, I find this activity very helpful for highlighting the differences between high, experimental, modernist, or literary prose and more “general” fiction. All types of fiction have their place in our reading worlds; this activity can help you see the differences between those types of fiction with greater clarity!)

Let’s dive in.

THE SETUP

You can simply read along to see how the activity works. Or, you can try it for yourself right now!

You may complete this activity digitally or by hand. For either approach, you’ll need the fiction you’re currently reading nearby so you can find a sentence to analyze.

Digital annotators:

Open a fresh Word doc, Google doc, or Notes app page

Get your book ready

Manual annotators:

Get a fresh sheet of paper — lined or unlined, it doesn’t matter (though I do love unlined for this exercise!)

Get a base pencil or pen to write with

Gather some colors to highlight and mark with — highlighters, crayons, colored pencils, all will do

Get your book ready

STEP 1: Choose a sentence.

This exercise will work for pretty much any sentence in the piece of literature you’re currently reading. For the best experience, look for a sentence that struck you in some way: look for something surprising, full of passion, or brimming with important details.

(My Age of Innocence readers: why not try this exercise with the first sentence of the novel? I’ll be close reading it, via this exercise, in Wednesday’s kick-off post. We can compare notes!)

If you’re having trouble choosing a sentence, flip to your favorite scene. Pick a sentence from that scene – any one will do – and try the exercise. If you hit a dead end, you can always try another sentence, or adapt the annotation to meet your needs.

STEP 2: Type that sentence in your document or write it in the center of a piece of paper.

Here are a few examples that I’ll use in our exercise today, from George Orwell’s 1984; Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice; and Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye — respectively.

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

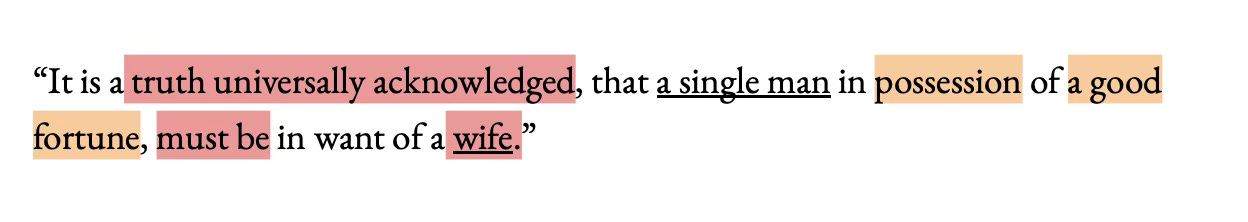

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

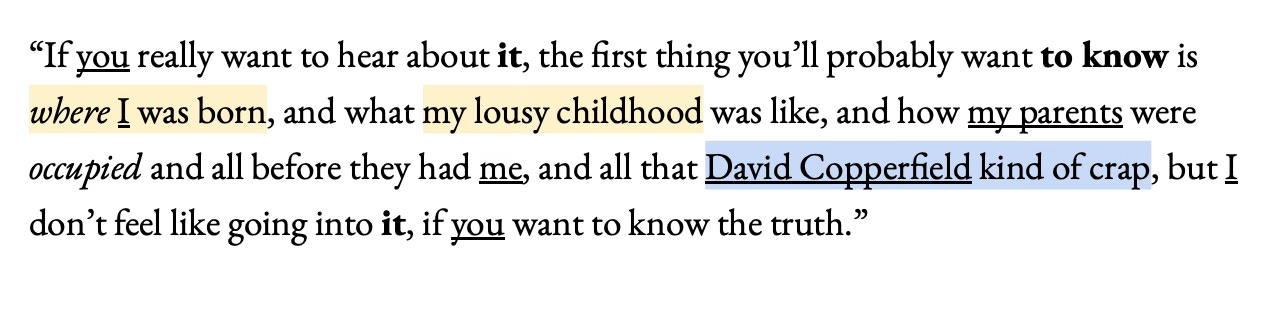

“If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

STEP 3: Annotate your sentence.

Use the categories below to apply annotations to your sentence, using bolding, italics, and underlining to note the basic story elements, and then using color to annotate specific themes. (You may adapt or change the themes I’ve selected here!)

Change the colors, as needed, to match your available supplies or to give you more options. Create a key for yourself to help you remember what your annotations mean.

So, here’s what that looks like for each of these famous first sentences:

STEP 4: Make observations and ask questions, based on your annotations.

Start by remembering this: You cannot be “wrong” with your notes; they will all reveal to you the ways you are reading the text.

So, look at your annotations. What do they show you — or make visible to you — at a glance?

In the first sentence of 1984, for example, my annotations help me to see that the sentence is a near-perfect balance of setting (in italics) and plot (in bold). The colors help me map to what the basic, central themes are — and what is missing entirely from this sentence. This sentence seems to be about: nature, time, and society. It has not yet mentioned any characters or people to hear the clocks’ strikings.

In the first sentence of Pride and Prejudice, my annotations help me very quickly suss out that this is a novel about society and economics. Yes, it’s a book about love and romance and marriage — but from the very first sentence, we see how deeply entwined those things are with social truths and economic realities. This narrator’s stance seems to be universalizing rather than deep into the particularities. Why does it matter that the book would start that way?

In the first sentence of Catcher in the Rye, I can very quickly note how this narrator puts themselves into comparison with existing literary works by contrasting themselves, and the story they are telling, to a Dickens’ character. This suggests something about ego and self-awareness to me. There are also a few characters named — “I,” “you,” and “David Copperfield,” so I get a sense of the narrator’s voice in a very loud way: they seem to be writing directly to me. I’m also drawn to the vagaries here: the multiple mentions of “it” that seem to suggest an underlying event or plot, but that I — as a reader — have no knowledge of or access to just yet.

Adapt or update your annotations as you dive into your observations. This is where you are building out your understanding — or reading — of the meaning of the sentence, and how that sentence has meaning in the context of the larger story.

For example: I’m wondering if I should highlight “want” in the first sentence of Pride and Prejudice, but would it be purple? Or red? This is helping me see the clever wordplay happening there.

It’s okay to change your mind about where and how you draw meaning, as you spend more and more time with the sentence(s) you’ve selected to closely read.

STEP 5: Closely read the sentence.

Now that you’ve visually mapped the many meanings and ideas packed into the sentence, and have made some primary observations about your annotations, write a summary of your findings.

This is also where you can begin to reach outward to make connections between the sentence you’ve diagrammed and the larger context of the novel in which it appears.

Search the internet or an encyclopedia for answers to the questions you asked in your observations, especially for words you didn’t know the meaning of (use a dictionary!) and places you’re not familiar with (reference a map!).

Here’s an example close reading, from the 1984 example.

I know, thanks to my annotation and observations, that I want to think about nature/biology, time and setting, and society. So, here goes:

1984 begins with multiple references to time. We’re given a specific day and time: a bright cold day in April, as well as the sound of time passing with clocks striking a new hour. But time is a construct, we know, and was standardized in the Western world to permit accurate departures and arrivals of trains. (It is not, compared to the bright, cold weather, a natural thing. It is human-made.)

So, we have a tension here between the natural and the unnatural, or the human-created or socially constructed.

This tension is compounded in the second-half of the sentence, when we learn the clocks are striking an hour not recognized in our society: the clocks are striking at a 13th hour; ours only strike up to 12 times. So: this 13th strike of this clock is our first real hint that we’re in a different “time” than the one we know currently, even though there are still months, like April, that we recognize.

So, we know and at the same time do not know the true setting in which we’re placed in the first sentence. We know only that we are surrounded by things that are natural, like the weather, and things that are unnatural, like clocks striking at strange times.

Pretty fun, huh?

STEP 6: Now, look for patterns

Now that you’ve closely read your sentence, zoom out to the larger context of the scene, chapter, or conversation in which the sentence appears.

Consider the following:

What has your close reading revealed about the larger scene?

What patterns does the sentence use that you’ve noted elsewhere in the novel? Does this sentence match those patterns? Evolve them? Break them?

How has closely reading this sentence helped you understand something in the novel better? (A scene, a confrontation, a character, a setting?)

STEP 7: Repeat!

You’re ready to repeat the exercise. Try it with the very next sentence following the one you’ve just annotated to see how the meaning builds. Or, flip to a whole new scene and compare the themes from one sentence to the other.

Pretty cool, huh?

If you gave today’s exercise a go, I hope you’ll share your findings or questions in the comments!

For the next 10 weeks, our reading group will be closely reading together, and every Wednesday, I’ll have a new chapter guide with historical insights, authorial background, and close readings to help us through the novel. Submit your early questions here.

Every Sunday, you can expect close readings and exercises unrelated to the read-a-long! You can make specific requests here.

‘Til next time!

This is one of my favorite posts - I have it saved in a special folder in my inbox so I can keep coming back to it!

OK. I have a question. I have been practicing my annotations (I just went back and studied the paragraph annotation post because I am a new reader here)... and I wanted to ask WHEN/HOW you go about defining the sentence/paragraph themes. As I try to figure out my own system, I feel like I have two potential paths.... a) do research ABOUT the book before i read and have a starter list of themes to look for OR b) underline as I go, keep a running list of themes and then once I am done reading, go back and use my colors to annotate + take notes.

I currently do b) and once I finish a book, I go back and read through my underlined parts but will definitely be practicing annotation, especially for my FAVORITE books! I just finished Giovanni's Room and I think it's a perfect candidate for this type of reading.