how to: closely read a single paragraph, in depth

[a step-by-step close reading of a paragraph from Cormac McCarthy's post-apocalyptic masterpiece]

Today, I’m sharing a step-by-step, close reading method that relies on single paragraph from Cormac McCarthy’s 2007 novel, The Road. If you haven’t read it, I avoid major spoilers and focus on the steps to close reading, instead.

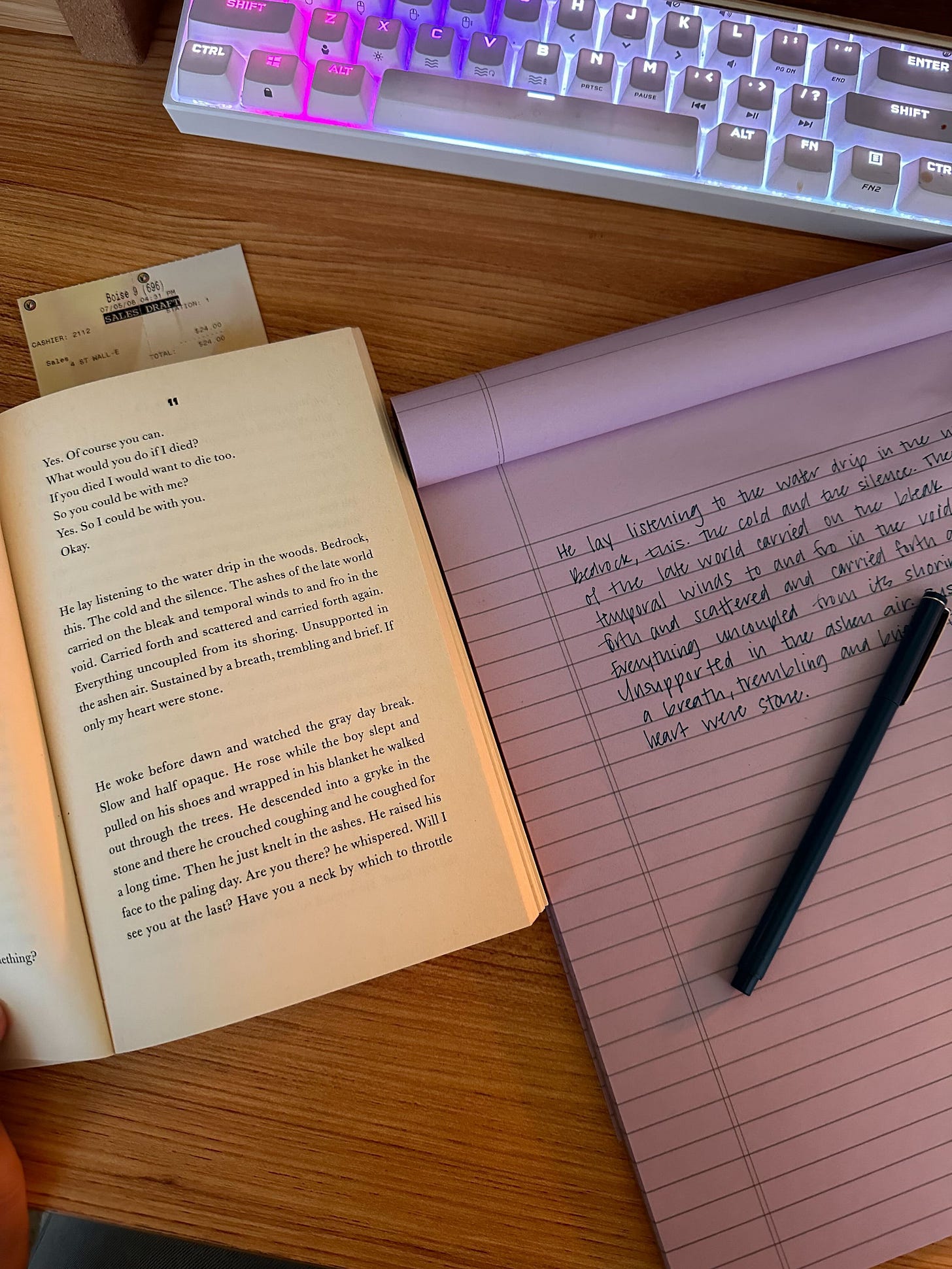

When I started college, I had a brick of a laptop that weighed 10 pounds and a charger that overheated to the point of burning my fingers when plugged into regular outlets on campus. (I feel old.) So, I did most of my close readings for my English and philosophy classes by hand, within the margins of my books or on notebook paper.

But even after upgrading to a featherlight machine and better writing software, I realized that no matter how good my digital tools were, and how easy it was to read books and articles on a screen, there was something about paper, handwritten transcriptions, and outlining my essays by hand that made them better. Deeper. More true.

I still feel that way.

And from my experience as a writing professor, I’ve seen that for many of my students, writing by hand and conducting a close reading on paper often yields a much more patient, and thorough, close reading.

Below, I’m detailing all the steps I took to annotate a passage that resonated with me as I read The Road for the first time a few weeks ago.

Step 1: Locate a passage you want to close read and transcribe it, word for word, on a piece of paper.

You can stop to do a close reading while you’re in the midst of reading a book, or you can mark a passage to return to when you’re all done. Either way, strive to select a passage that has some kind of resonance for you.

There’s all kinds of pedagogical advice about selecting passages with specific parameters—essentially, criteria that make a passage “warrant” a close reading. But I’d invite you to push back on the idea that what you would like to close read needs to check off certain boxes. In fact, I think that forcing ourselves to only consider certain types of passages or writing limits our ability to develop deep close reading skills.

So: when you’re looking for a passage to close read, simply start with something that stood out to you. Something you noticed. You don’t have to know why it stood out — you need only know that it resonated, made an impression, made you pause, gave you any kind of reaction (annoyance, anger, confusion, delight).

Remember the illuminating words of George Saunders:

“Criticism is not some inscrutable, mysterious process. It’s just a matter of: 1) noticing ourselves responding to a work of art, moment by moment, and 2) getting better at articulating that response.”

My reason for selecting this particular passage was that I remembered full phrases from it, even after finishing the book, days later. The final line in the paragraph I chose,“If only my heart were stone,” did something to me while I read. It broke my heart. It confused me. It also alerted me to the subtle, quicksilver shifts between the novel’s narrator and the main character’s mind. It’s a line that resonated — and that made it worth going back to.

A few tips for selecting your passage:

What sticks out? Consider the moments in the story that really resonated with you — it could be a fight between characters, a kiss, a fantastic description, a hilarious quip, a show-stopping costume. Anything you noticed.

Shorter is better. Short passages are best for this exercise because you’re able to focus on a much tighter, smaller moment in the story and go deeper into its construction and craft. Longer than 6 or so lines and you’re getting into unmanageable territory.

Step 2: Annotate the passage.

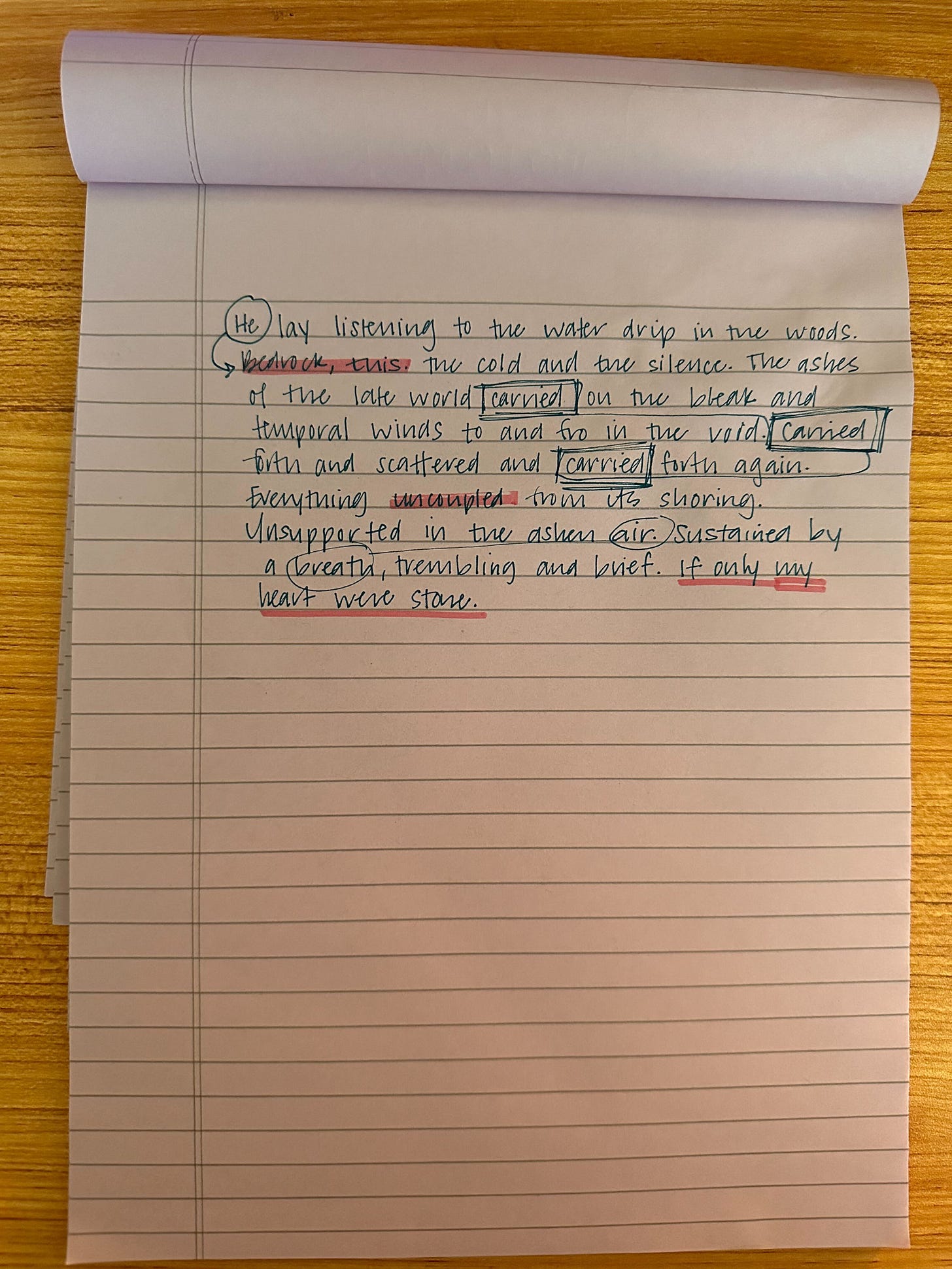

In this close reading, I used:

Circles to show words that stood out to me

Arrows to show where I felt movement or a change happening in the passage (in this case, the move from “he lay…” tonally shifts from an outward observation to an inward thought, “bedrock, this.”)

Boxes to show repeating words, with underlines to connect them

A highlighter to note what I felt were the “punches” of the passage — the places I noticed most, or felt most interested to look at more closely

Tips:

Make it yours. Use any annotation methods that are meaningful to you. I’ve seen people use exclamation marks, many colored pencils as highlighters/underlines, different ink colors, stars or squiggles, and more.

Make a map. You’re essentially creating a map of the text, so give yourself permission to traverse the passage like a visitor in its land. What does the passage make you feel? Is it heavy, humid, sticky, sad, funny?

Read it at least 3 times. In the above image, you can see that I’ve gone over the passage a few times, with a few different tools. Swapping tools or annotation symbols with each read helps guide each reading — so as you revisit the text, you find new insights or deepen your understanding with each read.

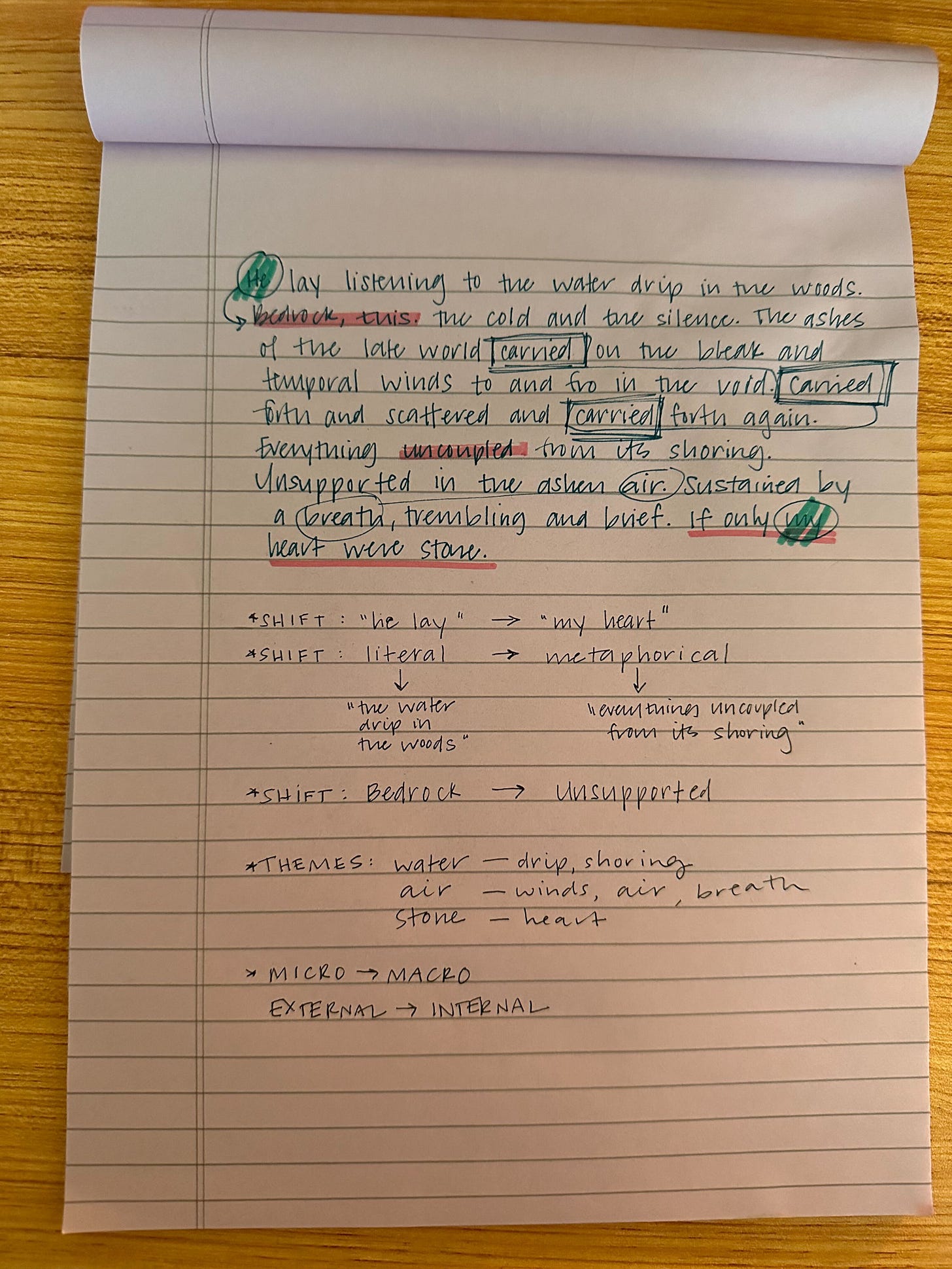

Step 3: Make a short, fast list of what your annotations point to.

Directly beneath your annotated reading, or on a new sheet of paper, start to summarize your annotations. Don’t worry about getting it perfect or unlocking some deeper mystery. Simply move from your annotations to listing “what I noticed.”

Here, the first word in my summary is “what I noticed” — a “shift” or a “theme” emerging — followed by the actual textual evidence of that noticing.

Tips:

Stay focused. If you find yourself making observations about things that are not evidenced in the passage, write them down in a separate list (maybe they happen elsewhere in the text, but this particular passage isn’t the strongest example).

For example: this novel is about a man and his young son. But his passage doesn’t mention his son, so I’ve avoided making connections to or calling in the son to a passage where he is not invoked.

In other words: avoid adding meaning as you write down what you’ve noticed. Let the passage mean what it means. You’re an observer, not an author, in this exercise.

Go back to basics. Maybe you’re noticing a lot of simple binaries or opposites (dark/light, big/small, loud/quiet) and think that’s not profound enough. I promise you, it is profound. There’s a lot of meaning, even in simple observations.

The goal of your close reading, here, is to really drill-down into what this passage actually does and the proof/textual evidence of where it does it. Stay focused and use your annotative language to center your reading and streamline your observations.

Literary critics or scholars get years of training in this step, specifically. This is the heart of closely reading: connecting textual evidence back to what has been noticed or called out as special, unique, or worth reading more closely in a text.

In the above image, you can see (in the black pen ink) where I’ve noted the following trends or unique moments I noticed in this passage. The first three are all moments of “shift” or movement in the text, where one idea morphs into another, related or opposed, idea:

A shift from “he lay” at the opening of the paragraph to “my heart” at the end of it. This shift in perspective and POV feels meaningful to me, as it mirrors the larger text’s constant movement from external observation to this single man’s internal, emotional world.

A shift from the literal, (“the water drip in the woods”) to the metaphorical (“everything uncoupled from its shoring”), which to me once again signals a larger textual pattern of moving from the physical reality of the external world—water dripping, the sound of the woods after a wet storm—to what that physical reality means or represents to the man experiencing it—that everything in the world seems to be “uncoupled” from whatever once held it stable. This shift illustrates the profound chaos of the text, and how the man is grappling with that chaos.

A shift in the language: from “bedrock” to “unsupported,” which aligns with the other two shifts I’ve noticed — the idea that what was once stable is destabilized, that the world has dripped into madness and entropy.

My other notes here point at themes:

I noticed the elemental and physical elements of the passage:

Water

Air

Stone

And how these elements shift from literal to metaphorical, like from wind to breath, or from stone to the man’s heart. All these moves mirror the “shifts” I’ve noticed, too. To me: that’s evidence of a master craftsperson at work — it’s evidence that how the story is written deeply informs what the story is about. Form and function, style and substance, are intimately working together here — a sign of McCarthy’s expertise and patience as an author.

And because I see these pieces of evidence working together, and helping me understand the novel better as a result, I also now I’ve struck gold: my close reading has yielded better understanding and deeper engagement with the story. It is making me a better audience for McCarthy’s work. (It is making reading even more fun than it already was.)

Taken together, these shifts and themes help me summarize my general “angle” or approach to this close reading: Finding the “micro” within the “macro” or the external’s impact on the internal.

Step 4: Identify an in-road and start writing.

Now that you’ve detailed your observations and a set of ideas about a piece of the text, you’re ready to begin a freewrite activity to bring these ideas together in a tight, close reading, of the passage (and maybe extend that reading into a larger insight into the text as a whole).

As the last part of step 3, I identified the general tenor of my reading of this passage — and it neatly aligned with how I might decide to read the novel as a whole.

To do the same, look at your close reading: your annotations and your summarized notes. What themes do you see in your own observations? Are you keyed into a specific idea, tension, or emotion? What would it feel like to center your reading or to focus your attention more deeply, onto that observation?

What would it feel like, in other words, to move deeper down that rabbit hole?

Start a 20-minute timer and then prompt yourself with this simple phrase:

“In this passage…”

Then, write about what happens and what you noticed, in this passage, based on the textual evidence you’ve gathered. If you’ve taken the notes, you are ready to create a conversation between what you read (the transcribed text) and what you noticed about it (all of your annotations and notes).

Creating that conversation is closely reading.

To see the close reading I ended up with after my own freewrite exercise, stay tuned. My close reading of The Road comes out next Sunday.

Re-reading this as a preparation for Middlemarch 😀I think about my undergrad days (too long ago to remember) when I did classes in English lit. It's going to be a mountain but the trek and the views are worth it

Thank you so much for this guide. I will most definitely apply this to my future reading notes.