"This poverty's arithmetic..."

Analyzing chapters 2, 3 and 4 of Yonnondio and getting into our next set of chapters

Welcome to the Closely Reading book club: a space where we closely read classic literature together and discuss assigned chapters each week.

As a reminder, here’s our reading schedule for Yonnondio:

Week 1: April 14-April 20 (complete, read the post here)

Read chapter 1

Week 2: April 21-April 27 (today’s post is about these chapters!)

Read chapters 2, 3, and 4

Week 3: April 28-May 4 (read these chapters this week)

Read chapters 5 and 6

Week 4: May 5-May 11

Read chapters 7 and 8 (end of the novella)

a content warning: Yonnondio deals with themes of child abuse, spousal abuse, alcoholism, and other forms of violence. The style of the story sometimes obscures, and in many ways amplifies, these themes. Please take care of yourself, as needed, while engaging with this text.

Let’s talk chapters 2, 3, and 4

Last week, we discussed the powerful opening chapter of the novel. In chapter 1, we get a portrait of a broken and unhappy family. But we also see bright moments of beautiful color and unexpected connection. We learn about colorful dreams and hopes for the future. We learn about their dream for a better life. Even as Mazie laughs in a sad and crazed way.

In this week’s chapters, we follow the Holbrook family to “a new life” on the plains, where Jim begins to work the land as a tenant farmer.

(Relatedly: I recently watched a Hulu horror film starring Sarah Paulson as a grief-stricken mother who attempts to make due during the Dust Bowl, after her husband moves to another state to take a job. I was thinking of this imperfect but intriguing film quite a bit this week as I read Yonnondio. If you’re a fan of suspense and/or Sarah Paulson, I quite recommend it!)

There are euphoric moments as the family drives to the farm. I was reminded of Cather’s rapturous depictions of the plains of the Midwest with the blue sky horizons and tall spring grasses.

But it’s all dashed through, here, with the pain of the Holbrook family’s struggle.

The fragmentation of modernism

Remember last week, when I said Yonnondio is a modernist novella?

Things got even more modernist this week, as the novel’s style not only continued on in its fragmented way. But the story itself posed a more overt challenge to dominant national narratives about The American Dream, poking holes in the idealized fantasies of working-class opportunity.

You see: modernist literature does this. It didn’t just poke holes in the old ways of telling stories. It poked holes in the old stories, themselves. It problematized them. Flipped them on their heads. Retold them from a new vantage. Undid their fantasies—the same way Will challenges his mother about their new life; he believes it’s nothing but a “fairy story.”

Modernist literature, in its stylistic choices, dismantles what we think we know about craft. About linearity. About how a story “should” be told.

It also, in its narrative and structural choices, dismantles what we think we know the truth to be. It unsettles us. Debates with us. Takes the easy way hostage; makes it harder—and perhaps more real—for us in its telling. That’s its modus operandi.

That’s why Olsen perhaps chooses to tell this story in this way. Under a lens of linearity and stark realism, Mazie’s story may lose so much of its impact. Don’t you think?

One of the hallmarks of modernist literature is the way it uses a stream of consciousness flow of thought to disrupt normative—or normalized—ways of thinking. It is, in this way, a reflection on the emerging machine age, that historical moment at the peaks of Industrial Revolution, when men like Jim Holbrook were often overpowered by the very machinery they used to complete their jobs. Were maimed often and killed routinely, all in the name of the gods of capitalism: productivity. Efficiency. Progress.

Fragmentation—lives lived on assembly lines, in mines, in coal dust—defines life for these working-class families. You can see it reflected in the way Olsen tells the story; form becomes function.

Consider the scene when Mazie and her younger brother discuss the confusion of their life:

Will came over. Lay down, his head snuggled on her stomach. “Five years. I’m five years old. What be it to be five years old?”

“Five years you’ve lived, Will.”

“Five years. I’m wearin your old coat, a girl’s coat. For why?”

“For that’s all there is. Shush now, let baby sleep. Shush, and hear the wind cryin.”

“The wind? What’s wind?”

“It’s people cryin and talkin.”

In the first chapter, we learned that Anna is desperate to give her children an education and a better life.

In these chapters, increasingly bewildered by the world—what it means to grow up, why there isn’t a coat for Will, what the wind is made of—Mazie and Will start to experience a multilayered education.

They learn about life on the plains in a vibrant and beautiful scene where Mazie yelps for joy, riding the raucous, wild wagon into the country with her father.

They learn about life on a farm as their “new life” settles in.

Mazie learns about books, stars, and the mysteries of the skies from her new neighbor, an elderly man who leaves his library to the Holbrook family—but which Jim sells for pennies when he learns he owes money to his landowner that year, despite having worked the land all year as a tenant farmer.

Mazie learns, in other words, more of the life lessons she learned in chapter 1. That good moments come—but they go, so quickly. Bad moments come oftener, as when the cuddling baby chicks roast in the fire by accident.

Hopes—even the smallest sparks of life—are dashed to ruin in a moment, in this world. The baby chicks become a kind of tragic metaphor for the home, don’t they? When Jim leaves, no one in the home thinks to check on the babies in the warming oven; when he returns home, there are no baby chicks to raise anymore. What of Mazie and Will? What fires are they locked inside, unable to escape out of their own helplessness?

There are moments of rapture:

“The farm. Oh Jim’s great voice rolling over the land. Oh Anna, moving rigidly from house to barn so that the happiness with which she brims will not jar and spill over. Oh Mazie, hurting herself with beauty. Oh Will, feeling the eggs and radishes gurgle down his throat, tugging the woolly neck of the dog with reckless joy. Oh Ben, feeling smiles around and security.”

This new life is tinged with rigidity, hurt, and recklessness.

This new life feels balanced until it tips off its axis again.

Winter is harsh. Old patterns return and another cycle of abuse begins.

Jim is ready to leave again—to start over again.

“What’s the matter, life never lets anything be? Just a year ago….I tried for us to have a good life.”

All this fragmentation—images of snow banks and charred chicks and nausea and butterflies behind the eyes. It mirrors a deeper, soul-level fragmentation in the people whose lives are torn apart by these ceaseless waves of pain. By this inability to get ahead, by a world stacked so firmly against their progress but so dedicated to making it their own fault.

What are you noticing?

As you get deeper into the story, what are you noticing?

What are you annotating?

What are you wondering about?

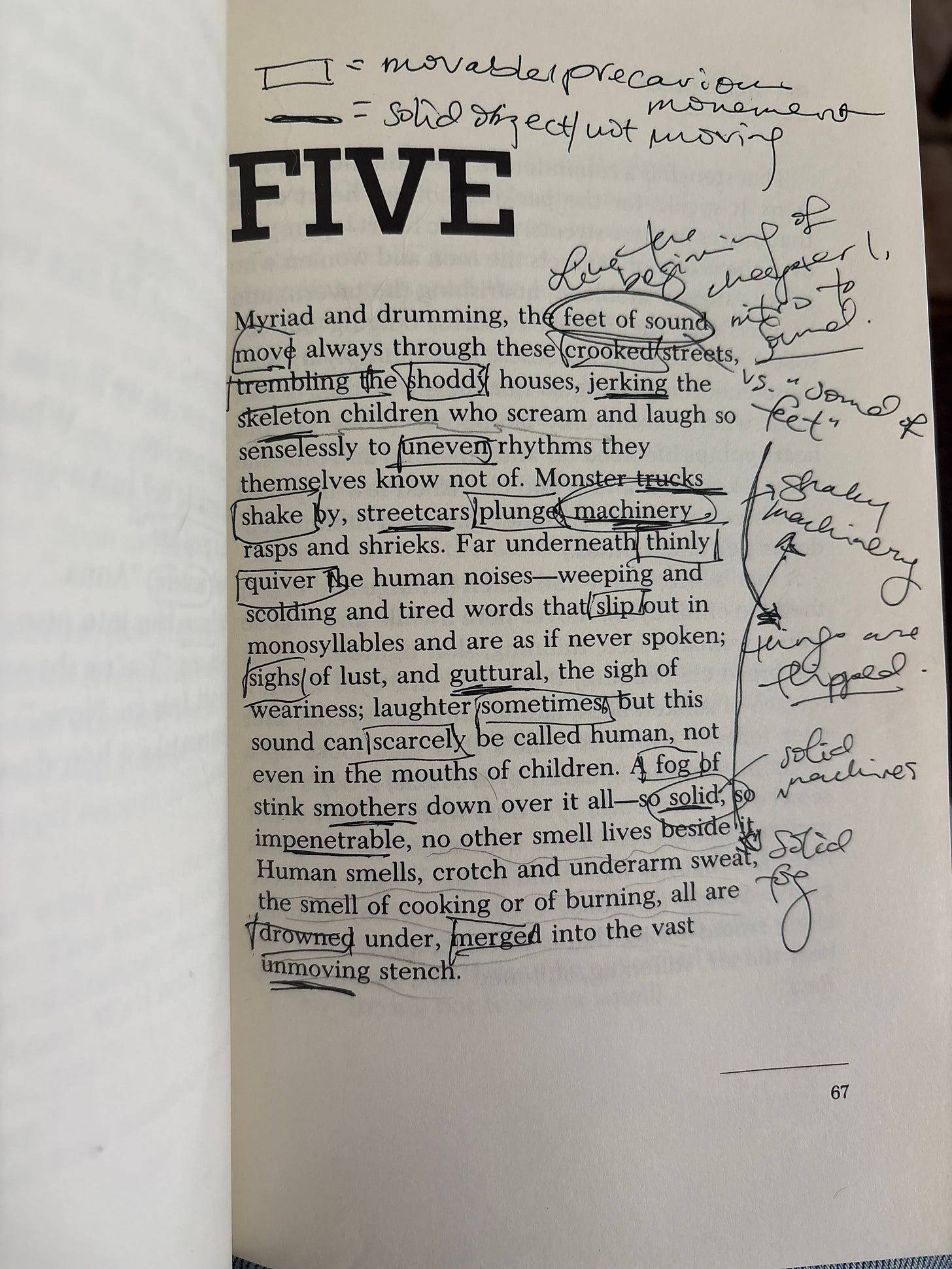

Bess, one of our readers, shared a photo from her annotations. I asked her if I could share it with you and she very graciously said yes.

You know I love seeing how people write in their books. I especially love seeing annotations in difficult and strange books like this one. I love the rhythm and frenzy of these notes from Bess—as if, like Virginia Woolf said of modernist literature, she is recording the atoms of her mind as they fall.

Bess uses boxes around words to annotate the “moveable,” or “precarious movement.” She likewise uses underlines to annotate the “solid” or “not moving” in the same paragraph. What a brilliant tension to focus on here!

This week, dive into chapters five and six. See how Bess’s annotations might inspire you —

The art of the Great Depression

A look at the art of Harry Sternberg // The Met on art from the Great Depression // Public art from the Great Depression // Social Realism and Art during the Great Depression //

And more amazing working class literature

Here are a few texts that come to mind when I think of working-class literature (and a few from the comments, as well—I love Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed and was thrilled to see it mentioned!)

The Hunger Games — a brilliant portrait of the way working-class individuals are treated by the Capital. Katniss Everdeen is a fascinating study in what working-class heroes look like, in literature.

Frankenstein stages perhaps the most fundamental of questions between a man and the product of his labor. The monster is, after all, the result of much labor on the part of Dr. Frankenstein. And, as Marx readily predicted, the alienation between a man and his labor creates a dramatic and life-altering dynamic for everyone involved.

Maid is one of the most beautiful miniseries I’ve ever watched, and it is based on a remarkable memoir that I’ve just begun reading.

And more…

Please note: if you decide to make a purchase via these links, a portion of your sale goes to me.

Thank you for reading with me!

I really love sitting down with my book each week, knowing that we’ll be coming together to discuss what is happening in each section. Thank you for inspiring me to pick up a great story, rather than doomscrolling my evenings away.

If you’d like to become a paid supporter, any of the tiers below are available to you. Simply click the amount to go to the page for that option.

$100 per year

Founding member status, or status as a “Patron of Literary Arts” is the highest paid tier possible—available for anyone who wants to opt-in at this level.$50 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $50. Available to all readers, all the time.$25 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $25. Available to all readers, all the time.$15 per year

Get a full year of Closely Reading for $15. Available to all readers, all the time.

For one-time contributions, you can buy my next cup of coffee.

One thing I am noticing is the tension between the embodiedness of the text (it is crowded with human smells and body parts, and not only literal ones: the sky has ears and flame has tongues, for example), and the way the fragmentation allows the reader to participate in the derealization or depersonalization of the trauma of poverty, which is a very disembodied feeling; there is a slightly numb, distanced feeling in the reading of it, that the characters also seem to experience (the most obvious one is Anna's state during pregnancy on the tenant farm). It's heartbreaking.

I like Chapter TWO,.

It's a melody of "sound of fear".

A melody charged with dread, tension; sound of fear, suspended in the air waiting for a tragedy.

"On the women's faces lived the look of listening"; "everywhere the sky and earth were listening , listening ", listening to this melody and fearing to hear the much feared sound.

I can perceive and deeply feel this melody :

"the autumn days brought always the sound of fear into the air"; "leaves dashed against the houses" "giving a dry nervous undertone to everything" ; a "maniac wind" "shrieked and shrieked" and "was whirring", and "was pitting the grass and leaves".

Suddenly the much feared sound, the shrieking whistle the tragedy.

A musical void , a mournful silence follow.

"...and the hush. ...No sobs, no word spoken.."

Attention shifts from the "sound of fear" to the silence of an " open grave".