Hi, all. I’ve been working on these ideas for a little while and I think this is a tip-of-the-iceberg type of essay — the kind of writing you do when you know you’re kind of still on the periphery of all the connections you feel are definitely there, but aren’t sure how to articulate yet.

You know that feeling?

I don’t usually like horror movies. At least not really horrific movies. But I’ve always been drawn to what feel like the more cerebral scary ones: The Sixth Sense was a gateway drug to films like What Lies Beneath, Get Out, Parasite, A Quiet Place, and most recently, The Last of Us.

Today’s essay is all about the latter, and it contains totally major spoilers for both the video games and HBO adaptation of The Last of Us. Proceed with caution, should you ever want to watch or play the series. And please know, I decided not to include any images of the zombies from the series, despite how incredibly amazing the art direction is, because they’re very very scary and I didn’t want to give anyone nightmares.

This essay, however, is not scary; it’s a philosophical dive into what Freud says about the particular kind of fear that zombie movies evoke. I hope you enjoy.

A horrifying story

The Last of Us follows two survivors — Joel and Ellie — in a post-apocalyptic hellscape filled with screaming gnashing zombies, warring religious and political cults, and tiny pockets of hopeful survivors hiding in the most unlikely places.

The game begins on an average September morning in the year 2003, transforming an ordinary day into the end of the world as we know it. The cordyceps infection — a fungal disease that turns human bodies into hosts for a raging, violent zombification — begins to ravage humanity. In mere days, the human population is effectively wiped out.

These horrific events take place just two years after the September 11th attacks and a year before the advent of Facebook would change the entire landscape of internet usage, social networking, and human connection. It’s a moment in history, then, when Americans were, with renewed force, suspicious of outsiders, entrenched in a “war on terror,” and not yet accustomed to getting their news — local, global, and otherwise — from a cell phone and their favorite TikTok creator.

The game never outright addresses this moment in history as a key context to its world building, but the timeline’s narrative effects feel clear: the zombie infection hits in a moment of political paranoia and disconnection, it renders our future world — the one we know and live in now — an impossible feat. And yet it also frighteningly mirrors the future we live in, at the very same time.

The Last of Us takes place in a historical moment of deepening anxiety and palpable, renewed fears of “the other.”

Like many zombie stories, The Last of Us stages the horror that we experience when we are confronted with the uncanny — which is a very specific kind of existential terror. When experienced as a video game, the story places you, as the player, inside repeated confrontations with repulsive, monstrous otherness.

For the majority of the first game, you play as Joel Miller, a hardened survivor who has been tasked with smuggling Ellie, a 14-year-old girl who is immune to the infection, to a hospital out west where a rebel political group is working on a cure. Like any good horror game, The Last of Us places you in repeated encounters with scary monsters and wild scenarios — and your only objective is to somehow survive.

In today’s close reading, I’m leaning on Sigmund Freud to help me understand the particular brand of anxiety and fear induced by the story — the uncanny — and to contextualize my shifting feelings about the end of the first installment of the story.

Calling Dr. Freud

Zombie games are ripe for Freudian analysis — all that biting seems like quite an oral fixation, right? But they’re especially ripe for analysis via Freud’s concept of das unheimlich, or the uncanny, on which he published a riveting essay in 1919.

For Freud, the “uncanny” is a “specific affective nucleus…within the realm of the frightening.” That is, the uncanny is whatever evokes a very specific kind of terror.

“The uncanny is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been familiar.”

From the German unheimlich, which translates as “not home,” or “unhome,” the uncanny is not simply the opposite of home, familiarity, and safety. It is the feeling you get when you realize that what was once home, familiar, and safe is no longer home, familiar, nor safe. (Freud’s essay includes five full pages of etymology for the term — in Italian, Egyptian, Latin, Spanish, and more — as well as a comprehensive timeline of the roots of the German term. He comes to the conclusion that “the uncanny” is essentially a Derridean Pharmakon: a word which contains its meaning, and the opposite of that meaning, in a single term.)

The point is this: the uncanny is the feeling you get when your home is no longer a home; that where you once found safety, you now find fear. The uncanny is that feeling that something that was supposed to one way turned out to be its opposite: like a creepy doll becoming animate, or some dormant version of yourself driving you mad.

The uncanny is what you’re experiencing when you are looking at a human, but it’s not a human anymore. The uncanny is a zombie.

An uncanny infection

In The Last of Us, there are many types of zombies, each more terrifying and less recognizably human than the version before, each representing the length of time infected.

In the early stages of infection, the infected remain eerily human. They walk hunched over, as if in excruciating stomach pain. They mutter and moan in distinctly human tones. Their brains haven’t fully succumbed to the infection yet, and so it is as if the person inside the infection is still fighting for survival.

As I play the game, stealth creeping through darkened hallways and cafes and schools, I shiver as I hear rogue phrases escape their mouths: “No, please no,” they shout as they charge at Ellie. “I don’t want to,” they screech as they attack.

I notice the pounding in my chest I have while playing is significantly amplified — a different kind of fear — when I am fighting zombies compared to when I am fighting other people.

In battles with FEDRA officials or Firefly fringe groups or cannibalistic cult leaders, I am simply in game mode. I breathe normally, muttering the occasional expletive as I blow my cover or fumble the controls. I like to play as stealthily as possible in all video games, so I creep around to find the angles and avoid killing as much as possible, entering large-scale battles only when forced by the game’s narrative.

“The uncanny is represented by anything to do with death, dead bodies, revenants, spirits, and ghosts.”

—Freud, “The Uncanny”

But in a battle with the infected, I experience a completely different kind of fear. My stealth is much less about strategic game play than about surviving and avoiding the terror of another threatening series of loud, bloody, exhausting fights.

Simply put: encounters with the infected put me into recognizable fight or flight mode.

My throat gets tight; my vision lasers; even my hearing heightens as I listen for any sign that the infected have begun to detect our presence. At a peak moment in the second game (much more violent than the first), my tongue actually starts to go numb and my hands tingle as I battle a series of new kinds of infected, each more existentially terrifying than the last. I realize, as I play, that I’m in the throes of a full anxiety attack.

For hours after taking off my headset, I jump at creaks in the floorboards of my home and keep more lights on much later than usual.

In these encounters, I realize I feel different because the fear itself is different. I’m experiencing the uncanny.

A way through the fear

In a session with my therapist, I explain that I find this whole thing fascinating — and strangely therapeutic. Instead of having a random, debilitating panic attack, I am instead having all the physical sensations of a panic attack, but I am completely aware of them. In some ways, I feel I am inviting them, am even in control of them. I could put the controls down and pause the game; I could restart the encounter any time I want to try again. I could step away from whatever is scaring me, breathe, think about my strategy, and go back in with a plan. I can act, instead of react.

“Horror can be a way to process our worst fears."

— Nathan Crooker // source

All of this feels weirdly revelatory. All of this feels so different to the types of anxiety and fear I normally experience, as a person with general anxiety and panic disorder.

I tell her that I almost didn’t bring it up, because I was afraid she’d tell me to stop playing. Instead, she encourages me to keep playing, because the games are helping me play out a linear experience of stress and fear: to become afraid, to experience the physical sensations of that fear, and then feel it resolve when the encounter or scene ends.

For someone whose body has always seemed to lack that last bit — who does not naturally have the ability to find chemical resolution, or to fully process anxious stimuli in a way that leaves me symptom-free — the continuous uncanny encounters in the game were perhaps teaching my brain what a different relationship to anxiety feels like.

The terrifying and unrelenting encounters with the undead in The Last of Us are showing my brain that fear and anxiety can be episodic, rather than constant. Resolvable, rather than lingering and intrusive.

"Viewers can immerse themselves in a harrowing narrative yet at the same time be perfectly safe, able to control the stimulus by turning it off or shifting attention to the surrounding space."

-Margaret J. King // source

The return of the repressed

In the final scene of the first game, Joel and Ellie are on their way back to Jackson.

Joel has saved Ellie again — this time, from the Fireflies who attacked the duo as they made their way to the hospital, separated them, and immediately sedated Ellie and took her into “surgery.”

When he finds out, Joel goes on a murderous rampage, killing every single Firefly in the hospital — including the surgeon and nurses — and stealing a car to get Ellie away from there as fast as possible. When Ellie wakes in the backseat, she’s scared and confused. “What happened? Where are we?”

And in response, Joel tells a big lie: Raiders attacked the hospital during testing, he tells her. They had to get out fast. And besides, there were loads of other immune people there and they can’t find a cure. They don’t need Ellie, after all.

Ellie, drowsy and confused, rolls over, hiding her face from Joel, and the story takes a new, unexpected turn into the uncanny.

“Uncanny is what one calls everything that was meant to remain a secret and hidden and has come into the open.”

—Freud, “The Uncanny”

In a pivotal scene, at the halfway point of the game, Joel tries to leave Ellie in someone else’s care and she breaks down, crying and angry, to tell Joel that with anyone else, she’d just be scared. She wants to be with him.

He decides to continue on their journey with her, and their dynamic forever changes. During the final stretches of the game, it is clear that Ellie is no longer “cargo.” She has become Joel’s home as much as he has become hers. They have become a family.

But then, Joel lies and Ellie knows it.

As they finish their journey back to Jackson, Joel is more open than ever. He talks about his beloved daughter, who died in the first night of the outbreak. He imagines their new life in Jackson. He seems lighter than ever, even moving with an agility that he lacks in the final few battles, through which he hobbles and limps. They are finally headed home and it’s clear Joel is actually excited, perhaps for the first time we’ve ever seen him as such.

But Ellie walks slower than usual. She’s quieter, too, no longer making witty jokes or stupid puns to entertain Joel. And as Jackson comes into view, Ellie calls ahead to Joel.

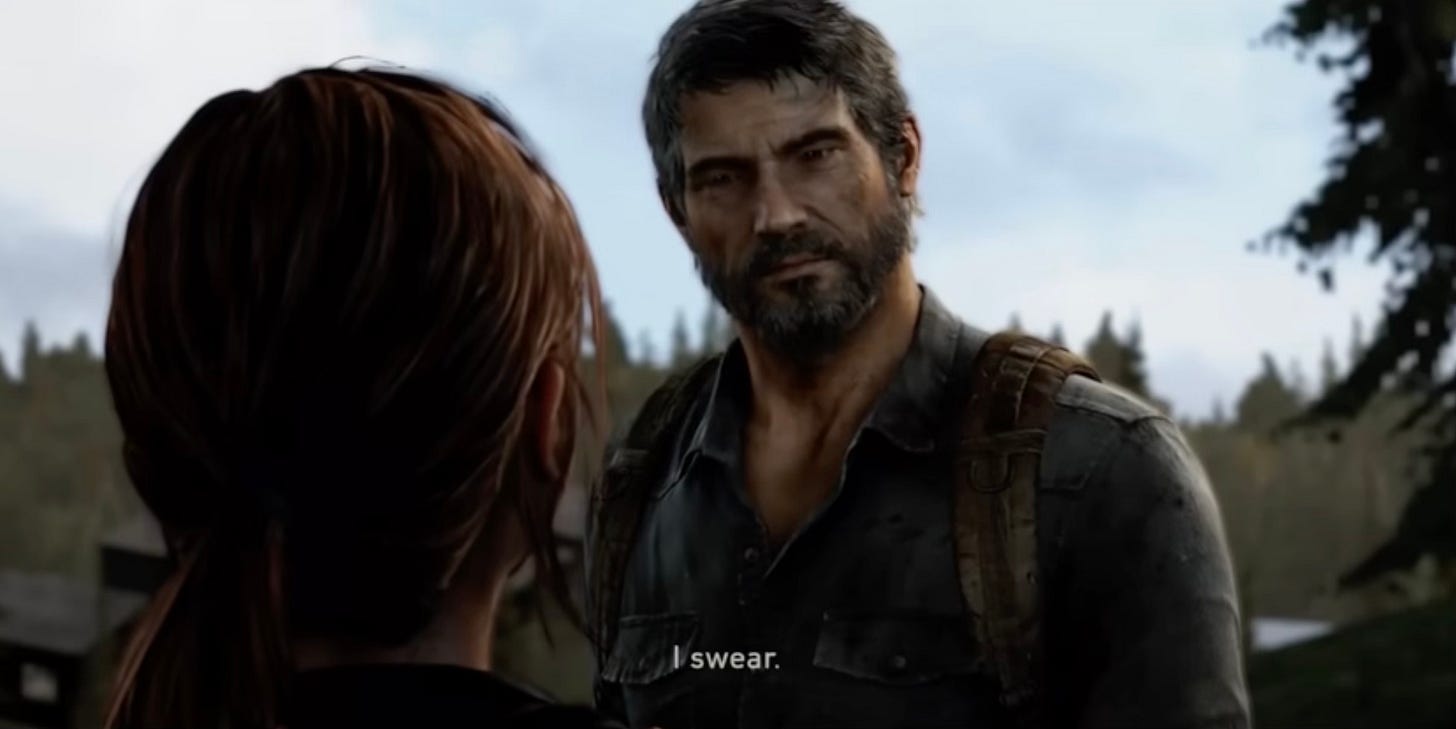

“Swear to me,” she says. “Swear to me that everything you said about the Fireflies is true.”

Without hesitation, Joel answers: “I swear.”

We watch Ellie’s face sit in a kind of numb neutrality; far from the expressive, boisterous personality we’ve enjoyed throughout the game, she is withdrawn. She is deciding whether or not she believes him.

Her eyes drift from his in the final shot of the game and with the tiniest nod of her head, she mutters a quiet, unconvincing, “Okay.”

Freud’s essay on The Uncanny helps me unpack this tense moment. While the essay introduces one of the best theories for understanding zombies, I believe it’s also an apt theory for understanding that inner battle — the confusion and gaslighty energy and disbelief that accompanies the terror of realizing you have misplaced your trust.

Because I think what happens in this scene is that Joel’s big lie unhomes Ellie. It decenters her. The trust they’ve established, the understandings they’ve reached, the mutual knowledge they’ve shared — all of it is jeopardized with Joel’s lie. Where Ellie once felt safe and finally at home, as if she had a chance at a family life again, she now feels contradiction, even fear. She feels she has to make a choice between the truth and comfort; between reality and home.

I don’t know that Freud would sign-off on this reading at all — he’s rather insistent that the uncanny is always the kind of terrorizing blurs between reality and fantasy that fiction conjures best — but I find the concept of the unheimlich so helpful in understanding the subtleties of Joel and Ellie’s relationship: the precarity of their connection, the dire experiences they’ve shared, the hope they both harbor in one another and in the future.

Joel, who does not believe in the Fireflies’ ability to find a cure, decides to find a future, and to make his home, in Ellie. Ellie, who believed her immunity could save the people she loves, decides to believe Joel’s lie — at least for a while.

(There is a second game, and a second season of the show, after all.)

“The uncanny that we find in fiction — in creative writing, imaginative literature,” (and, may I add, perhaps in some video games,) “actually deserves to be considered separately,” from the uncanny experiences we may have in our real lives, Freud says. “It is above all much richer than what we know from experience; it embraces the whole of this and something else besides, something that is wanting in real life.”

This is because fiction can elevate and hyperbolize our lived experience.

“The writer can intensify and multiply this [uncanny] effect far beyond what is feasible in normal experience; in his stories he can make things happen that one would never, or only rarely, experience in real life. In a sense, then, he betrays us to a superstition we thought we had surmounted; he tricks us by promising us everyday reality and then going beyond it. We react to his fictions as if they had been our own experiences. By the time we become aware of the trickery, it is too late: the writer has already done what he set out to do.”

This is perhaps what happens to my anxiety when I find myself, in Joel’s huge boots, stepping into a field of angry infected: I am in a false world that is a familiar mirror of the world I know. There are road signs and cars, birds and buildings. There are people, too — and then there is “something else besides,” all those terrifying zombies, all those impossible ethical dilemmas, all those heightened questions of what it means to “save who you can save” at the end of the world.

This is perhaps what happens to my anxiety, too, when I find myself in Ellie’s shoes at the end of the game, slowly following a man who has lied to me up a long hill, to our makeshift home in a dilapidated town, filled with desperate strangers. A man who is promising me the impossible “everyday reality,” we might have in the gated, well-protected town where infected no longer roam free.

I react to Ellie’s fiction as if it had been my own experience — and by the time I realize I’ve related to her, and that I, too, have stopped trusting Joel, who I have also been and have been complicit in helping to reach this place, “it is too late.” I have entered that familiar, unfamiliar site of the uncanny — I find myself in the dark hallways of feelings that are mine, but that I did not create or ask for. I find myself experiencing all the sensations of my anxiety — all the physical realities of my body’s signals for defense — and feeling, for the first time, that I know they are not mine.

This — this impossible feat, this uncanny evocation — is the power of good storytelling. It stages impossible questions of what it means to be alive in a world where violent zombies lurk and loom; it mirrors the world I experience in the throes of my worst anxiety attacks with shocking fidelity.

It displaces me and it centers me. It heightens me and it grounds me. It is “so much richer” than my everyday reality, but it also tells me something about that reality. Its crystalline suppositions about the end of the world are those rich fictions against which I learn to feel my way through the worst of us, the best of us, and the last of us — and know that against all the odds, despite what my anxiety is telling me, I’ll probably survive.

Thank you for reading.

If you have an idea for a future essay — about a specific piece of literature, a type of literary theory, or anything about academic writing and research — please do let me know on this Google Form.

‘Til next time