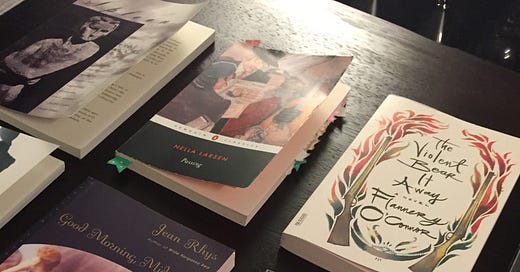

start Nella Larsen's Passing today

why I picked this novel, plus a sentence-by-sentence close reading of the first paragraph

Dear friend,

I have something to confess. I originally had Passing slated for next spring.

But when I plucked my heavily annotated copy off the shelf and started reading…I decided to hell with waiting…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Closely Reading to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.