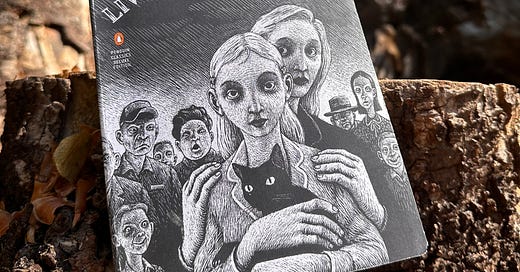

Shirley Jackson's haunted homes

themes to read for in "We Have Always Lived in the Castle" and "The Haunting of Hill House" this october

Hello, dear book club friends.

This week, if you’re following the fall syllabus, we are embarking upon two of Shirley Jackson’s best-known novels, and the ones you’re probably reading all about, all o…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Closely Reading to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.