"she is all affability and condescension"

Pride & Prejudice | Week 5: Vol. 2 chapters 1-6 | on the arrival of spring, Rosings Park, and the inimitable Lady Catherine

Welcome to the Closely Reading book club: a space where we closely read classic literature together and discuss assigned chapters each week.

Hi everyone! I took advantage of my long holiday weekend, so I apologize for getting this guide out a bit later today. I’m really excited to share it with you!

Later this week, I’m hoping to share a bonus post for paid subscribers about my day spent at the local university, going through all their Austen books!

Welcome to week 5 of our Pride & Prejudice read-a-long!

This week, we’re reading Volume 1, chapters 1-6. If you’re reading an edition of the novel with continuous chapter numbers, it should be chapters 24-29. (I’ve updated our official schedule with the continuous chapter numbers for you!)

If you have not completed our chapters for this week yet, I encourage you to do so before reading today’s guide. And please remember to avoid spoilers in today’s comments!

We also have loads of questions from readers this week — I love how closely you’re all reading. This was a really fun guide to create. Now, let’s get to it!

Or, you can leave a one-time contribution.

“Hope was over, entirely over,” states our first chapter this week, as Jane and Elizabeth toil in the ache of disappointed love. The Bingleys have abandoned Jane and Mr. Wickham’s attentions have shifted to a young lady (Miss King) who is about to inherit a helluva fortune.

In chronological order, here are some highlights from this week’s reading (with new characters in bold):

Charlotte marries Mr. Collins

Jane goes to London

Elizabeth goes to Rosings to visit Charlotte

Elizabeth, Charlotte, Mr. Collins and their party dine with Lady Catherine, her sickly daughter Anne, and Mrs. Jenkinson (Anne’s governess, who has stayed with the family and attuned herself to their every whim—what an awful job, right?)

Lady Catherine interrogates Elizabeth about her upbringing and education, as well as the fact that all 5 Bennet girls never had a governess and are all out in society (meeting men, taking proposals) at the same time

When I started thinking about the books I wanted us to read together this year, I knew Pride and Prejudice was at the top of the list because of how many of you had asked to read it together.

What I didn’t know was which analytical lenses I wanted to emphasize in our reading to help us explore the novel in more depth together. As I selected our other readings for this year, I started realizing I was really interested in the idea of social classes and class distinctions—as well as how individual people within society experience, or notice, those distinctions.

I knew Pride and Prejudice grappled with such things, and was absolutely delighted to see how much the presence of Lady Catherine seems to elevate this theme into everyone’s consciousness in the novel (and outside of it) in this week’s chapters.

Before we meet her, Mr. Collins anxiously assures Elizabeth that it’s okay for her to wear the best, albeit simple, dress she brought with her on her trip to their fancy dinner party. For, while Lady Catherine knows she is “superior” to all those in attendance, “she likes to have the distinction of rank preserved.”

In other words: Lady Catherine likes being the richest and therefore highest ranking individual at the table — and she likes to be able to see that distinction in those around her. Lady Catherine, that is, likes being surrounded by people who are not as wealthy, privileged, or socially superior as herself, and she likes to be able to feel and see the differences in their clothing, their manners, and their personal histories.

In fact, the language of the chapter (Volume 2, chapter 6 — or chapter 29 if your edition uses continuous chapter numbering) emphasizes the gaps between the Bennets, Gardeners, and Collinses (and Jenkinses!) of the world and the de Bourghs.

The party “ascended the steps into the hall,” quite literally rising in the ranks of social elegance, as they move through an architecture designed to celebrate wealth. They move through an entrance hall, then through “an antichamber”—or antechamber, which in a Regency home was something like a smaller dressing or waiting room—until they finally reach the sitting room where Lady Catherine, her daughter, and Mrs. Jenkinson await them.

Notice: Elizabeth (and the others) must ascend to the place where Lady Catherine sits and waits. And as she welcomes them, Lady Catherine is mindful “not conciliating…such as to make her visitors forget their inferior rank.” That is: Lady Catherine is kind—but not so kind that she makes her guests forget who’s in charge.

Lady Catherine dictates, bosses, judges, instructs, and advises throughout the dinner, taking great pains to share what a benefactress she really is and how much she goes out of her way to “advise” and lead those within her community.

And yet, even as everything in the Rosings estate is designed to intentionally remind these visitors of their inferiority to Lady Catherine’s grandeur, we get a significant line about how Elizabeth experiences this stunning concentration of class distinction:

“Elizabeth found herself quite equal to the scene.”

What a beautiful and simple way to remind us readers that Elizabeth—for better or for worse—does not ascribe to the “place” or the role she is intended to occupy in society.

She walks when she ought to take the carriage; she declines a dance invitation when she ought to be flattered; she refuses to marry a man who cannot make her happy. And here, at Rosings Park, she feels herself equal in a setting that is meant to make her feel less than.

Here are a few ways to get into some deeper analysis this week.

Choose your favorite sentence from this week and write it down on a separate sheet of paper. Analyze each word, as we did with the first sentence during week 1. Flex that sentence-level-analysis muscle.

Create a list of the “classes” of society we’ve met in the novel thus far by putting some of our key characters in “order” according to their import, based on their social class. You may decide to include:

The Bennets

Officers/militia

Darcy

Bingley

Collins

Lady Catherine

Once you do this, ask yourself: how do I know where to put everyone?

Every week, I share my favorite sentence. And I invite you to do the same in the comments.

“sometimes dirty and sometimes cold, did January and February pass away.”

This isn’t a very exciting sentence—and that’s perhaps exactly why it resonated with me this week. It’s dirty and cold in my neck of the woods and hope has been hard to come by. I laughed out loud when I hit this line in Volume 2, chapter 4 (or chapter 27) because I was struggling to find the motivation to keep reading and taking notes and, frankly, to care about anything even remotely more difficult than cookies and reality TV.

Austen’s humor brought me right back into the story in precisely the way I needed to keep going.

This is my very loving reminder to you that if you’re struggling to keep up, or to focus, please know that’s such a normal part of closely reading. It can be so pleasurable, yes, but also deeply taxing. If you’re hitting a brick wall with some of these chapters, remind yourself that it’s normal, you’re not a failure, and the pages will be waiting for you after a cuppa tea or a nice walk or a day off from reading. And then remind yourself this book is supposed to be funny.

Questions galore this week! How fun!

I am addressing many of them here; some I will save for next week, for the sake of length and for being able to answer with a little bit more context....

Question 1

What is the deal with patronage? How is it that Lady Catherine gets to assign Collins as the minister? Collins does have the advantage of the eventual inheritance of Longbourn, but without that wouldn't Charlotte be at risk of Collins losing the patronage of Lady Catherine and thus being thrown out of the rectory? Is this really such a solid living as Collins exclaims it too be?

Answer 1

This is a great question—and something that’s a little mysterious in the novel. We don’t know exactly how Collins secured his place with Lady Catherine, but after meeting her this week, I’d say his endless praise of her may have something to do with it.

You’re right that it’s really not a very stable or solid living, despite his declarations otherwise. Collins is entirely at Lady Catherine’s will and whim. But he fancies himself such a deeply loyal servant (of Lady Catherine first, and the Lord second, I think we can safely say, haha) that he’s placing his faith intentionally. It’s very unlikely that he’ll actually inherit Longbourn, so he’s putting all his chips (or his “fish,”) on flattering Lady Catherine and keeping himself and his family in her good graces.

Question 2

My question concerns the Netherfield ball. I never quite understood why Mr Bennet was frowned upon for interrupting Mary. "Lizzy had looked at her father to entreat his interference" and later became "sorry for her father's speech". Yes, it was a problem that he had to do that in the first place but would it not have been more of a problem if Mary had been allowed to continue? Do you think it was the way he did it? Appreciate your thoughts on this matter thank you Haley.

Answer 2

Nice close reading here! I think it’s mostly uncomfortable all the way around because it’s a no-win situation. Mary won’t leave the darn piano to any other ladies (which perhaps signals that her parents have failed to teach her good manners) and now her father (who, as we know, is loathe to abide social rules and be told what to do) has to embarrass her in front of everyone.

I think there’s also a layer here that might ping on the Bennet family’s growing reputation of being desperate for proposals. Mary staying too long on the piano is an unfortunate signal that the Bennet girls are looking for social spotlight (even though it’s not clear this is Mary’s intention, it’s what the other ladies seem to take away). Time on the piano is time for a young lady to show off her “accomplished” status, and Mary overstays her welcome. So when her dad has to tell her to give another girl a chance, he also makes the Bennet family even more visible in their embarrassing string of social faux pas.

I’d love to know if others (including you!) have other takes on the moment.

Question 3

If we've been told exactly where the town of Meryton is located, I've missed it. Apparently it is near but not too near to London. The basing of a militia there for the winter provides an injection of single men into local social life and so into our story, but I don't understand politically why there should be soldiers in this small town in the country. They seem to just be idling there.

Answer 3

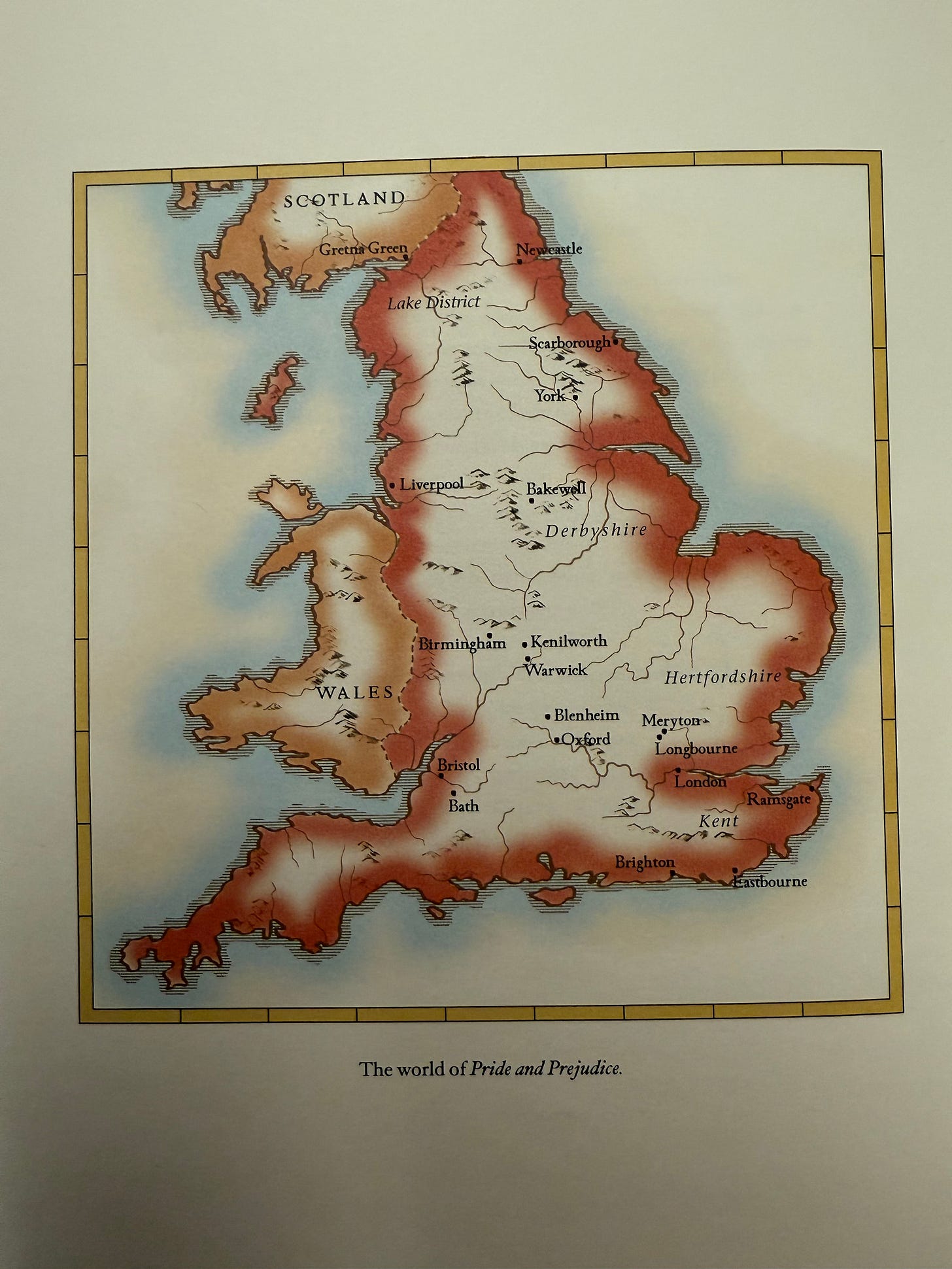

You’re in luck! I went to the University of Utah’s library this weekend and hung out in the Austen stacks—and I found a map.

I’ve also been doing a bit of reading on this. The novel is set during the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815), when England was at war with France—and that’s why the militia arrives in an otherwise peaceful (and isolated) part of the country. You can read more here (but beware of major spoilers!!!!!!)

Question 4

I've noticed in some novels now, I think they're all British, or maybe in Virginia Woolf's, that they often don't use full place names. They use ----shire or even just ----. I noticed it in Pride and Prejudice when Jane travels to see Charlotte (I know you told us to read slowly and enjoy it, but I just can't stop, I'm more than 2/3 of the way through a book at the time of writing this question). Is there anything to it? I did a bit of googling and Longbourn, Netherfield Park, Pemberly and others are imaginary, set in real places like Sussex and Kent. So why the need to sometimes use ---- if she could just make up places like she did with the estates? Often she could just leave it out or write the sentence differently as it is not important to the plot or character.

Answer 4

This is a great question, and the map above may be of interest to you, as well. Basically the answer my professors shared with me during grad school was that giving too many local specifics could be jarring for readers in that time period, and while Austen is writing a pretty strict realism here (that is: real people in a real place experiencing realistic/non-magical events), being too literal with names of places could be disruptive for readers. For example: imagine readers in a real, named place taking issue with the accuracy of representation. By using a generic/nameless place, Austen saves herself—and readers—the pain of having to make too direct a comparison, while still getting to gesture at the idea of a named place or a change in location.

There may well be other takes on this, so I’m happy to update the answer as I learn more.

Question 5

Hi Haley. Your post on Free Indirect Style reminded me of this essay “Narrating” by James Wood from his book How Fiction Works. What was more interesting was the word “tolerable,” which you talked about in your Week 2 post. James Wood spends about a page on Free Indirect Style in Pride and Prejudice, and he briefly talks about the same word: “What is, or would be, a ‘tolerable’ fortune? Intolerable to whom, tolerated by whom?” He suggests the word “tolerable” belongs to Sir William Lucas in that passage, not to the author. But, as you mentioned in your post, the word “tolerable” is used so many times in the book. I don’t have any particular question. I’d love to hear if you have any further thoughts on Free Indirect Style and the word “tolerable” and who the word belongs to.

Answer 5

Hi! I love this — and thank you so much for linking to the essay for our readers. I can’t wait to read it, myself!

Rather than directly (pun!) answer your question…I’d invite you to dig more here. You’re bringing fantastic closely reading energy to the word “tolerable,” and I don’t want to overly dictate where you’re headed.

For what it’s worth, though, I think the word “tolerable” isn’t necessarily “belonging” to any individual in the novel; I think it’s a concept, rather, that the novel is interested in exploring. By that I mean that Austen uses the word so frequently that it feels meant to be noticed and wondered about. For me, the word brings up questions like you’ve referenced above: tolerable for whom? Under what circumstances?

Why is “tolerable” sometimes an insult (as when Darcy says Lizzy is “barely tolerable”?) Is it ever a compliment? What’s the difference between toleration and enjoyment? What does tolerability have to do with knowing one’s social position and abiding the rules? (What can Elizabeth, specifically, tolerate? What is outside the bounds of her tolerable levels of accommodation? Think: refusing Collins’ proposal.) For me, “tolerable” seems like a very intentional finger pointing at the idea of social spaces and what you’re meant to “tolerate” based on the position you’re born into (and perhaps also the one you marry into…)

Question 6

Hi Haley, I'm enjoying so much this exercise! Could you please explain to us this saying that Lizzy says to Darcy when in chapter 6, she quotes this saying: "Keep your breath to cool your porridge". Thank you!!

Answer 6

Of course!!

Lizzy is basically saying “don’t waste your breath.” As in: you can keep talking, but it’s pointless. You’d be better off using your breath to cool down your hot breakfast.

This phrase is actually attributed to Austen, as her own invention. It wasn’t a saying of the time, but it sounds like it became a bit of a popular saying after the novel was published!

Want to submit a question for next time? Here’s the form.

WEEK 6 | Monday, February 24

Read volume 2, chapters 7-14

(Continuous chapters: 30-37)

Off we go into more chapters!

This week, I spent some time at an academic library (it was so fun and SO nostalgic!!!) and added a few more recommendations to my titles on Bookshop.org. I’ve also begun an academic bibliography for the novel, which I’ll release to paid subscribers once we’ve completed the novel (scholars hardly ever write a spoiler-free analysis, after all).

The full schedule is available here:

Thank you for reading with me

I so appreciate your support, no matter what tier you’re at. Every Like, Comment, and Share is an unbelievable honor—and helps this community continue to bloom.

If you’d like to explore your options to becoming a paid subscriber, there are both monthly and annual options available for you to peruse.

If you’re a student (or grad student) with a tight budget,

please reach out to me for a special offer.

Meet me in the comments

Here are a few questions to help you get started.

What was your favorite part?

What was your favorite quote?

‘Til next time…happy reading!

The class hierarchy is clear. Status attaches to land ownership, so the order of operations is as follows:

1. Darcy—owns a large estate but doesn’t have a title, so he’s landed gentry. Derbyshire is up north, so he’s rural—the closer you are to London the higher status.

2, Lady Catherine—landed BUT she is called Lady CATHERINE, not Lady de Bourgh. Lord/Lady first name is called a “courtesy title.” Austen’s readers would have been able to place her by that detail. I am putting her below Darcy for a couple of reasons—one is her courtesy title, and the other is that she’s got a daughter to marry off—she wants to merge the Darcy and de Bourgh holdings, but clearly Darcy is in the driver’s seat here. She needs him to agree to it, and her daughter is described as “sickly.” A landowner needs at least one son to survive into adulthood if he wants to keep his landholdings.

3. Bingley—also landed gentry, but it’s implied somewhere his status is more recent.

4. The Bennets—landowners, but not nearly as large a holding as Bingley or Darcy. Mrs. Bennet’s brothers are “in trade” so she’s clearly lower status than her husband, and her lack of social grace is used to point that out.

Now we get to the landless. The second and subsequent sons of the landed don’t inherit anything, but they can’t just go out and get a job. The second son typically would go into the church, and after that the family would have had to purchase a commission for any remaining sons.

5. Mr. Collins

6. The officers

7. The Gardeners and the Jenkinses—since they work for a living they are at the bottom of this hierarchy.

There are other clues here. We are told that the Darcys and the deBourghs are “old families” and their surnames are more Norman than old English. “Bennet” is also Anglo-Norman. Collins is old English. “Gardener” and “Jenkins” are right out.

Austen deftly skewers the pretentions of the people who inhabit the same community as the Bennets. In chapter 27-Lizzie is in a coach with Sir William Lucas and Charlotte’s younger sister Maria, heading off to Kent to visit the Collins’s. They plan to stop in London to see Jane.

“(Maria)…..a good humored girl, but as empty headed as himself (Sir William), had nothing to say that could be worth hearing, and were listened to with about as much delight as the rattle of the chaise.” Elizabeth loved absurdities, but she had known Sir William’s too long. He could tell her thing new of the wonders of his presentation and knighthood; and his civilities were worn out, like his information.”

Lady Catherine is sketched as quite grand and intimidating, but the 19th century English reader would instantly understand that these are small-time country people—the real nobility is probably a couple of layers above even the de Bourghs. Sir William was presented at the Court of St. James and received a knighthood, but it is clearly not a hereditary knighthood—and it’s the biggest thing in his life. These knighthoods were handed out pretty routinely and didn’t have any land or money associated with them. Our Queen, Dame Judi, received one of these.

I think I have reached peak nerd here so I’ll stop.

“What are men to rocks and mountains?”

-Elizabeth Bennet

I found it interesting that Lizzy was so upset that Charlotte chose Mr. Collins for “worldly benefit”, but when Wickham dumps her for Miss King, she defends his actions to her aunt. “A man in distressed circumstances has not time for all those elegant decorums which other people may observe.”

I found out Darcy’s first name is “Fitzwilliam” lol

Mr.Bennet continues to be enjoyable; I like how he knows Jane’s situation better than her own mother and has insight into Wickham’s character as well: “He is a pleasant fellow, and would jilt you creditably.”

I can see an (inverse?) parallel between Mr. B spending as much time as possible in his library with Charlotte encouraging Mr. Collins to spend as much time as he can in the garden.