leaving academia, whatever that means

why I write and what I'm trying to accomplish here and how to measure it

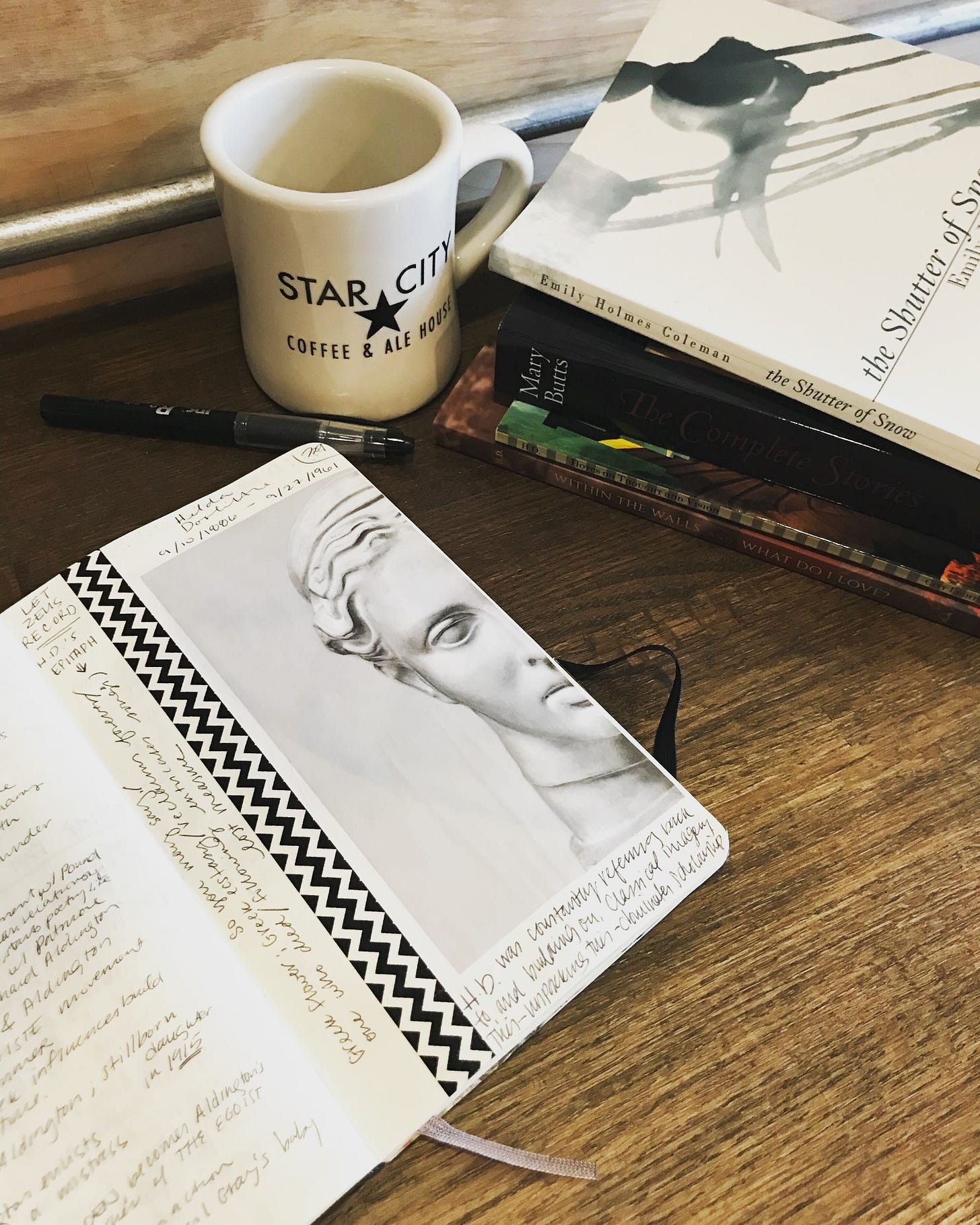

I originally started this Substack as a space to do the kind of writing I missed after finishing my PhD and “leaving” academia. I wanted a space to write and share close readings: miniature essays about books and stories that try to make sense of them in some way, or offer some new way of looking at the patterns or weirdnesses in them.

Then, I started writing miniature “how-to” guides or lessons on specific reading or writing practices. I’ve written personal essays a few times, too.

And I guess I still can’t really figure out what it is I’m doing here, in this space. Which is maybe a microcosm for the larger sense of loss I’ve experienced since leaving academia. I can’t really figure out what to do with all these ways of thinking and reading and, frankly, being that I learned from being a scholar for most of my adult life.

Sometimes it feels like I spent all that time building toward a self-imposed dead-end. After all, I’m the one who decided not to go on the academic job market and to seek other career paths. I was tired of the precarity and the absolutely shit pay and constant pressures to do more “for the CV” — to create committees and start new initiatives and volunteer all of my time to support my beloved English departments, and to do so eagerly, with a smile, with no expectation of reciprocity in the form of job security or benefits or salary.

I think I’d had some deeper hope, back when I started this Substack, that it’d somehow magically provide some answers. As if the very act of writing essays and feeling “academic” each week by writing about literature and pedagogy would perfectly fill the little chasms in my heart from leaving academia. And it hasn’t, though it does feel very good in many other ways, and maybe that’s making me reflective and ruminative.

Way back, during my undergrad degree, I was lucky to have professors who were realistic about the academic job market for English PhDs. They never, ever deadened my hopes or told me not to go to graduate school. But they were real with us about the long, difficult road(s) ahead.

They told me that tenure track was an increasing rarity, that the job market was not only grueling but downright nonsensical; that there were lots of professional pathways an English major could lead to. I knew I had options, in other words.

“Leaving academia” never felt existential or terrifying to me as I know it does for many others because “becoming a professor” never felt like the only meaningful pathway I could take with my career and my future.

But during my PhD, I really started to feel a whole rhetoric of shame around non-academic career exploration, and I regularly experienced a total dismissal of other careers by my colleagues and almost all of my professors. It made me feel out of sync with my peers and frustrated with the lack of imagination around what our degrees could mean.

This pervasive suggestion that academic life was better and more worthy than any other career path, seeped into everything. It was a narrative of exceptionalism: I can’t number the times I was told by professors that the market was tough, but I was an “exception” because of whatever characteristics or dedication they’d noticed in me, during a single semester of knowing me. I got tired of hearing I was “special.” I just wanted a job in a system where we were all welcome; where it wasn’t just the “exceptions” who should keep pushing forward.

This narrative of worthiness and exceptionalism was the undertone of almost all of my coursework; it was the theme of “professionalization” events and exam preparation workshops. And even though I could identify it, and stay alert to its presence, it still started seeping into me, too. It bred anger and insecurity, a feeling that I didn’t know what was best for myself, and for the first time, I genuinely began wondering if I could ever even be happy outside of academia. After all, I was continually told that I was “born to be a professor” or “made for the academic life,” but if that were true, then why did it make me, and so many wonderful and smart people around me, feel so insecure and replaceable and undervalued, almost all of the time?

If I was made for this, did that mean I was destined for pain?

If academia made me feel this way, what was I staying for?

I started realizing that all the persistent messaging about academia being a superior lifestyle, meant only for those who proved their devotion through borderline self-ruin came from persistent fear and confusion.

But it was neither my fear nor my confusion to carry.

By the time it was my turn to study for exams and take the next step in my PhD, I was sad about how quickly my time as a grad student was passing. It was flying by and I was heartsick. I was also broke and exhausted and sitting through 4-6 hours of training and coursework each week about publishing and building my teaching portfolio in which I was reminded, over and over again, that there were no jobs but that I was special — there’d be a job for me. Somewhere. Eventually.

Maybe it’d just take 1-5 years on the job market. It would take however long it took; “the ones who stick around get rewarded with a job, eventually,” a professor told me, “because everyone else gives up.”

I started reframing my dreams of a big, exciting future as “giving up” on academia. And even as I felt myself do it, and told myself it wasn’t true, it still felt true. God, it felt like a harsh truth that would haunt me if I ignored it.

My program was a place where the graduates who’d seemed to magically transform their degrees into tenure-track positions were regularly welcomed back to the department to give lectures and host workshops and hand out advice. Those who hadn’t gotten a tenure-track teaching or research position were not. We simply never heard from them again. It was literal hushed tones in hallways to speak of their departures from academia; it was a complete dismissal of reality, because the fact was that the majority of them didn’t have any luck on the job market and had to find work elsewhere. Had to take another path.

I got really fed up with never hearing about these other paths.

And I found myself in an “all or nothing” environment, where leaving academia was equivalent to giving up, or admitting defeat, or finally revealing to everyone what a liar you were all that time they thought you were the exception. It was admitting I wasn’t special. That I wasn’t “made for this,” and that I was not, in any way, an exception to the harsh rules of the system.

Eventually, I worked my way out of this horrible way of thinking by continually giving myself experiences in non-academic spaces and letting myself enjoy them, by proving to myself that I was not a sell-out or someone who gave up. I was simply someone, like millions of other academics before her, who chose another future.

And I guess that’s where I started thinking, when I started writing today: I went in this big circle of thinking and believing and when I sit and wonder about what it all means or how my “leaving academia” journey has changed or how my feelings have evolved…it all just comes back to the fact that I still really don’t know. And I know I don’t have to, but gosh, I long for some clarity around why I’m writing close readings and sharing academic-ish writing online.

I don’t always know what it’s for. Who it’s for. Why it’s important.

(And despite all that, some of you are still here, subscribed and reading and leaving comments. And I wish I could look you in the eyes and thank you for that.)

My full-time job is content planning and strategy for big brands, so you’d think I’d have the basic premises figured out around here, but why is it so much easier to do things for others? To put work first?

I’m reminded of one of Carroll’s many lovely riddles in Wonderland: “She generally gave herself very good advice, (though she very seldom followed it).”

I help companies identify what their content is, who it’s for, why it matters, what it is meant to do for them. Yet I’ve struggled to really enforce a content strategy for myself, here. And maybe that’s the problem. Maybe I want a personal space that doesn’t feel so “planned,” or “strategic,” and maybe I am wanting to write without the constraints of a brand or a business around my ideas. Without having to say that any of this is meant to drive any kind of brand goal or content program.

I keep toggling between questions of what I want to write and what I’ve learned determines high performance or “drives ROI” or gets Likes or Shares or Comments…or whatever. And I’m so tired of those factors waving so loudly in my mind. Tired of how much any effort to “be online” inevitably sparks questions of transforming yourself into a brand or monetizing your efforts or connecting your various platforms under a single umbrella, and all those other things that don’t, in the end, signal all that much. Not really.

Maybe I want to share writing that, critically, is not content.

So, maybe I need a new framework — not the same one(s) that work at work or for big brands or for marketers — to help me keep all these goals alive. I’m not sure what that will look like. But I’m excited to find out, and excited to have you along for the journey.

When this landed in my email I set it aside. I didn't want to read it. Perhaps I wanted to read it when my head was clear and I could form an immediate response which your writing so deserves.

Thank you for putting words to the chasm that forms after the degree and being the odd one out. When everyone else is looking at you with disbelief and pity. 'Then why did you do PhD in the first place?' Seldom do they understand it's a way of life and not a vocation. For me, it is. There isn't a time stamp when I stopped being a biochemist. I will always be a scholar of proteins. You will always be a scholar. No matter what the world pretends to tell itself. No matter how we utilise our online writing spaces or blogs. And I absolutely understand what this space means for you (even though no experience of literature in academia at all- this bifurcation of arts and sciences is anyway ridiculous) and I hope you continue to think, write, analyze, discuss, and grow in any form you want to, academia or not.

P.S. Three years since I left academia and it has been the most stimulating three years. Peaceful too.

I made the same decision 15 years ago when I quit a toxic post-doc to work at a software company.

I have no regrets when I get together with old friends who stayed in academia. Their careers forced them to stay focussed on their narrow fields. They are the experts in those minute fields, but they have no outside interests. They haven't grown as people or experimented or tried new things - just written papers, taught classes and chaired committees.

I love that I can be on the PTA at my kids' school, do a qualification in bookkeeping, take up competitive quilting, be a first aider at work, or run a hobby farm (just not all at once!)

Leaving academia has given me far more opportunities to learn and grow. I think it has also made me a more interesting person.