"it is such a rough, ungainly thing"

a short, scholarly argument about Yonnondio and Life in the Iron-Mills

Hello, dear reader.

Today’s bonus post is a short, academically-tuned exploration of the final scene of Yonnondio. It closely reads Olsen’s text by keeping an eye on its similarities to the Rebecca Harding Davis story that inspires it.

It is followed by a comprehensive works cited list you can reference, should you be looking to do some of your own research.

I hope you enjoy.

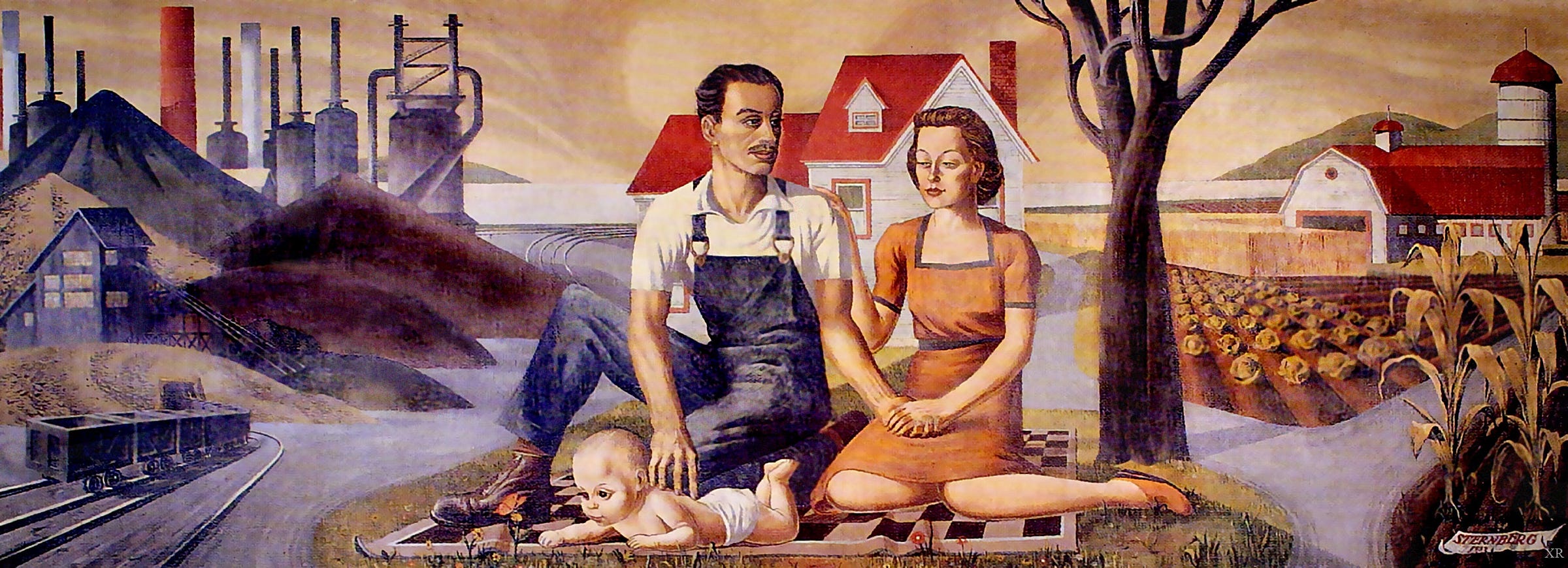

The final scene in Yonnondio takes place during a heat wave in summer, in which Anna’s family is subject to living without any cooling comforts; they are simply too poor to afford any relief.

In her kitchen, Anna sits with her youngest daughter Bess in her arms, “peach and amber jars of jelly and fruit cover every surface,” and she once again sings (190). The text states that “It is all heat delirium and near suffocation now,” and the scene feels desperate—though Anna is surrounded by a kind of artistic creation in her canning jars, it is yet another day in the life of this poor, unhappy family.

“Bang!”

The scene is interrupted. Bess has picked up a canning lid:

“Bess has been fingering a fruit-jar lid—absently, heedlessly dropped it—aimlessly groping across the table, reclaimed it again. Lightning in her brain. She releases, grabs, releases, grabs. I can do. Bang! I can do. I!”

Here, like her sister collecting treasures in the dump, like her mother’s compulsion to cook and clean, Bess is compelled to move, to work, to make.

“That noise! In triumphant, astounded joy she clashes the lid down. Bang, slam, whack. Release, grab, slam, bang, bang. Centuries of human drive work in her; human ecstasy of achievement, satisfaction deep and fundamental as sex: I achieve, I use my power; I! I!...Heat misery, rash misery transcended.”

Olsen employs a modernist hallmark here: the catalog or list. By listing the sounds and the actions of this human drive—bangs, slams, and grabs—she calls attention to the transcendence of the achievement, the way the noise—“the human drive” takes Bess beyond the heat wave.

Here, from the raw materials of her mother’s domestic labor—her creation of jam in fruit jars—Bess, with “centuries of human drive” at work in her tiny body, is compelled to act: to make noise, to create sound. Like her mother’s whisper, her unuttered cries, her singing, Bess wants to break the silence. Then, in the midst of her noise-making, Will—Anna’s son and Mazie’s brother—brings in a radio.

“They hear for the first time the radio sound” and Mazie hears it, “floating on her pain; like the spectrum in the ray, the magic concealed; and hears in her ear the veering transparent meshes of sound, far sound, human and stellar, pulsing, pulsing” (191). Anna, seeing Jim outside in the dusty heat, “urge[s] him in,” though “she yearns to be out into it” (191).

While there is certainly more to say about the presence of sound in this ending—building on the attention to music and sound we discussed last week—I am more interested in how Anna and Mazie react to these sounds: to Bess’ need to create sound, to the radio, and Anna’s desire to get out of the house “out into it.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Closely Reading to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.