📚 how to understand an academic article

Part 2 of 4: literary analysis works with patterns; here's how to identify them

Welcome back to this free 4-part series about how to grow more confident in reading academic articles. Today, we’re diving into part 2.

📖 Don’t panic. Do pause.

Welcome back to our series on reading academic articles.

Today, I’m recommending 4 steps for your academic reading practice, designed to help you pause and plan as you enter a literary analysis — and help you avoid the heart-sinking panic that can arise when you start to feel overwhelmed by the density or unfamiliarity of the prose.

In fact: my biggest piece of advice today lives within the broad spectrum between peace and panic.

You don’t have to “get” everything in an academic article on your first read. What matters more is how you deal with incomprehension.

Do you get angry and defensive, defaulting to calling the ideas wrong or stupid because you don’t understand them or haven’t heard them before?

Do you get withdrawn or frightened, feeling overwhelmed or foolish for even trying?

Do you get a zap of energy, driving you deeper into the confusion so you can puzzle it out and find out how the pieces fit together?

Do you get bored and decide it’s not worth your time?

All of these are completely natural and normal responses to the unknown; it can help to know which arena (including the many possibilities I have not covered here) you’re likely to fall into. That way, you can pause before reading and remind yourself how to take on the reading challenge ahead.

Step 1: Recognize your approach and adjust for it

Here’s a basic invitation, based on the four (common!) states above, and all built out of experiences I have had with real writing and literature students that helps them stay the course during times of incomprehension or confusion.

Angry?

Remind yourself the ideas did not come into existence to change your mind or force you to alter your life or your decisions. Use the defensiveness you’re feeling to encourage yourself to comment as you read and leave margin notes, noting where you felt threatened versus where you felt challenged.

Try this reframing:

“I don’t like this” → “This is helping me better understand how other people consider these ideas or questions.”

Sad or scared?

Remind yourself this essay was written down because the author wanted a reader. Even if you disagree or dislike the essay, the author wrote it in pursuit of conversation. They want you to read it. They wrote it to be read!

Try this reframing:

“I don’t get it, I’m hopeless” → “I’m actively learning a whole new way to think through this idea!”

Energized?

Rock and roll, my friend. Be cautious not to leap too quickly back to your own project; pause throughout the essay to make sure you’re catching what’s on the page, and not just what you’re bringing to it.

Try this reframing:

“I am so excited, this is the best thing ever!” → “Taking my time can be a meaningful way to sustain these feel good vibes, my dude.”

Bored?

Set a timer. Read for 12 or 17 or 4 minutes. You can decide when enough is enough, and because you’re not my actual writing student, if you give up…well…there’s no final grade around here.

Try this reframing:

“Ugh this is literally so boring and I am going to scream” → “I can try for 7 more minutes. If I’m still feeling stuck when my timer goes off, I’ll have a piece of chocolate and move onto my next task.”

Step 2: Start with a strategic skim

When you first open an article, resist the urge to read it line by line or to start busily annotating and start with a curiosity pass.

Here’s the order I recommend:

Title and abstract – What’s the article about? Circle words that repeat or sound theoretical (desire, structure, narrative, temporality, ideology). They’re often clues to the main ideas the author is exploring.

(Especially in the digital age: titles are the keywords that ensure an article is findable online by the right people!)

Introduction (first 1–2 pages) – Look for a sentence beginning with “I argue that…” or “This essay contends…” — these are signposts that your author is positing their thesis upfront and early. Without reading too deeply yet, can you tell what the basic gist of the article will be?

Section headings – Look for section headings or breaks. Notice how the article is structured. Are there additional keywords you want to circle or notice?

Conclusion – Yeah, it’s a major spoiler alert moment but it doesn’t hurt like fictional spoilers do. Knowing where an essay lands can be a helpful way to ground yourself in what the essay is working toward from the start.

This can be a way to ask yourself: How are they going to get from A to B?

At this point, you haven’t even read the article yet — but you have identified the key ideas, the general thesis, and where the essay lands. These are helpful structural supports as you get into the deep read.

Step 3: Follow the pattern!

Once you’ve got the basics identified, it’s time to follow the argument more slowly. In literary scholarship, most paragraphs have a rhythm:

claim → evidence → interpretation → connection back to the thesis.

Your goal is to track that rhythm, not to memorize every citation or to catch every single nuance.

So here’s an annotation tip: try bracketing the argument and bringing it back to basics. Within the margins of the page, next to the paragraph, you can use simple letters to nod to the building blocks of the argument, or you can put full brackets around the sentences or paragraphs that accomplish these bits:

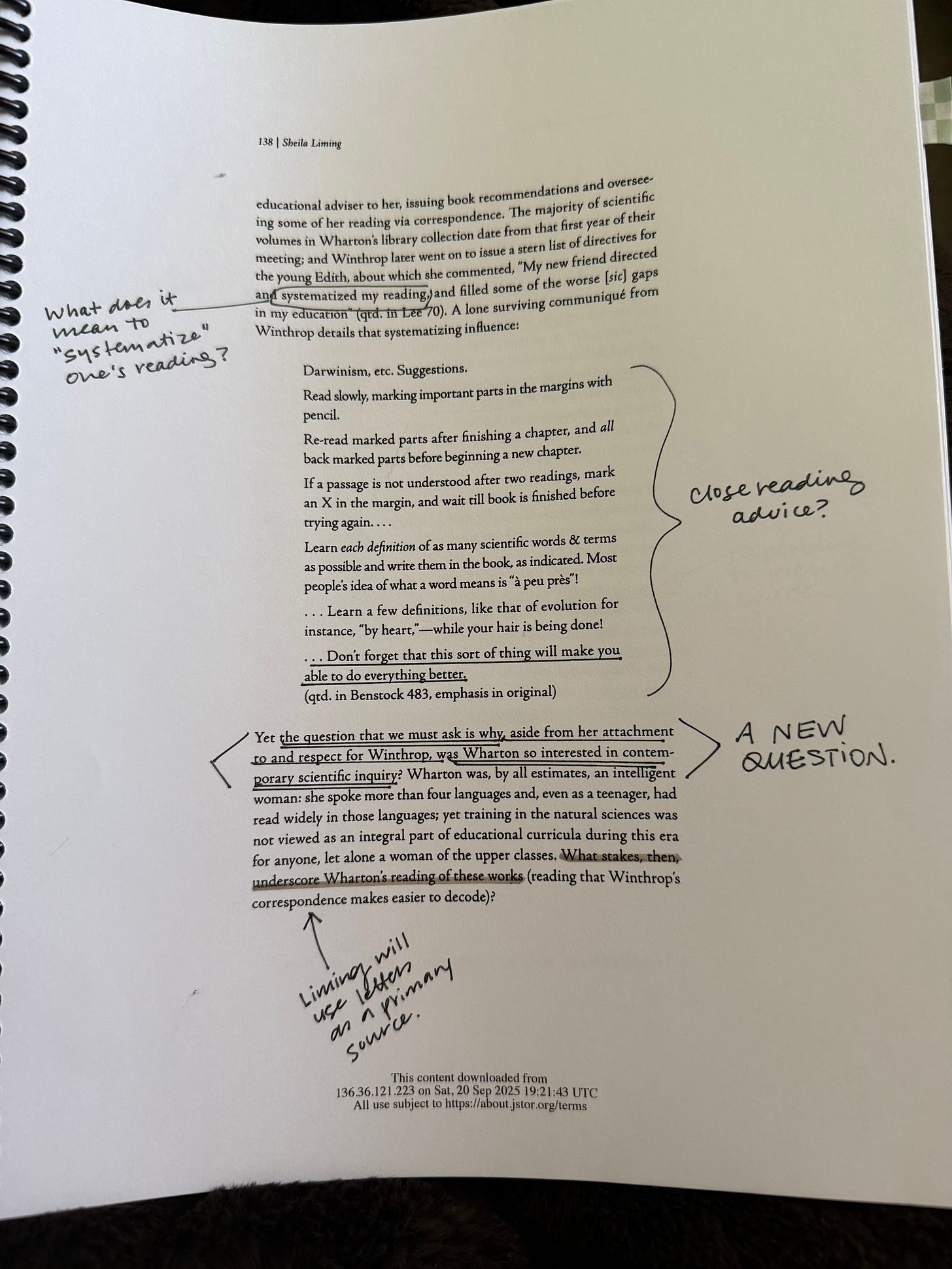

[Q] = the author’s main question or new questions that arise

[A] = the author’s answer or claim, or places where overarching takeaways are posited

[E] = example or evidence, like a close reading of a specific scene or a quote from another scholar

[C] = connection to the broader idea, or a link back to the main thesis — you might notice that A + C happen together frequently!

This is one way to outline the essay for yourself, so you can see the pieces in motion and, when you’re done, come back to key moments to see how they were crafted.

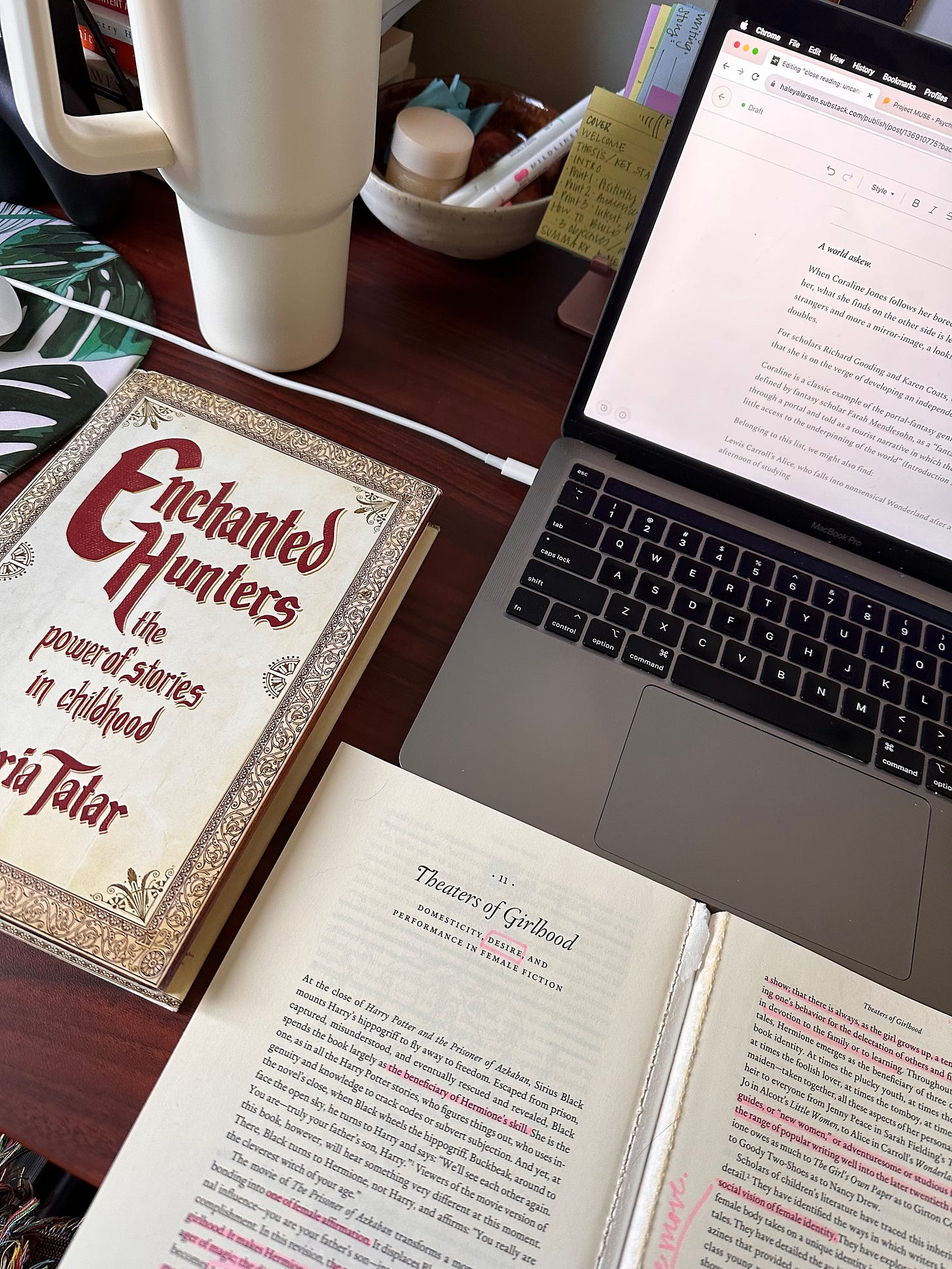

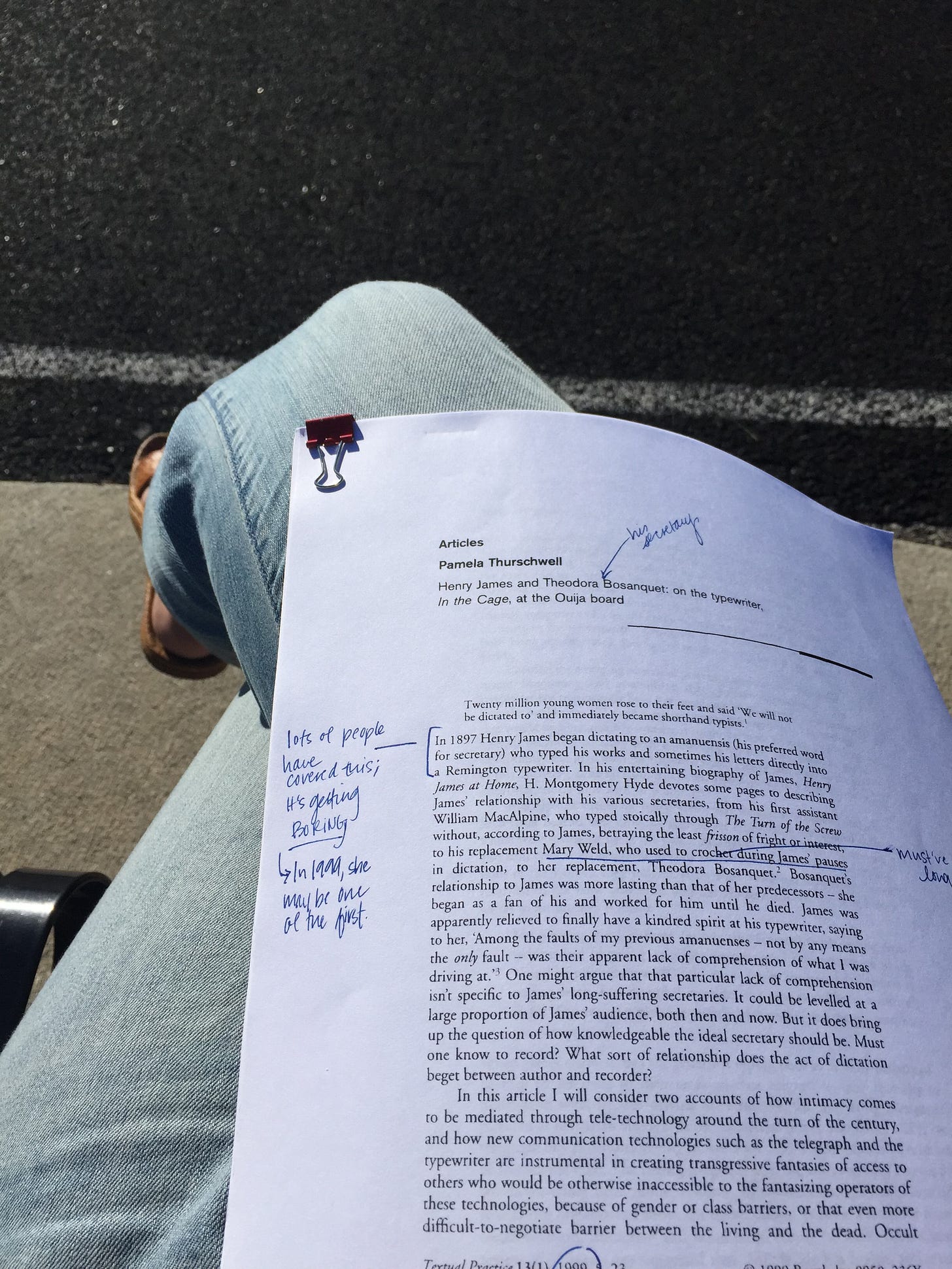

See the image below: I used triangle-shaped brackets to mark where I saw the author of this article positing a new question.

Step 4: Reflect on what resonates

Once you’ve skimmed and summarized, take one more pass — not for comprehension, but for identifying what has resonated most with you.

Ask:

What words or phrases keep repeating?

What kind of voice does this scholar have — cautious, assertive, poetic?

Where do you feel tension or excitement as you read?

Where do you get lost? Where do you get found again?

This is where reading scholarship becomes enjoyable. You start to understand where craft decisions were made, and how they’re not always made in service of the argument, but can also be made in service of style.

(And then, you’ll start to develop your appreciation for the scholars who deftly marry the two!)

You might start to notice that writers like Eve Sedgwick treat literary analysis more like a novelist might, while bell hooks writes as if she’s penning a brilliant manifesto. Some critics write like detectives or investigators (like Foucault!); others write like they’re lecturing in the most engaging literature course you’ve ever taken (like Jia Tolentino!)

Tone has the power to lift jargon from tiresome to telling, and remind us that density can sometimes (often!) be a marker of a great respect for precision.

Speaking of jargon…

Underline any word you don’t know.

Guess its meaning from context.

Write a plain-English substitute in the margin.

When in doubt, grab your handy dandy Dictionary of Literary Terms. (I love this resource so much!)

A mini-exercise for you.

Choose one paragraph from a scholarly article you’ve been reading this week. Then:

Read it once, nice and slow. Try reading aloud to really slow yourself down.

Next, rephrase the paragraph in your own words, on a separate piece of paper. Imagine you’re really stripping the ideas back, as if explaining to a friend who has zero context.

Now, rewrite the paragraph a second time. This time, focus on finding the middle-ground between the author’s original phrasing and your stripped-back version. Think about elevating your version into something more elegant and personalized.

Doing this type of voice movement teaches you to move between registers, which is truly a core skill of literary interpretation.

📚 Build your scholar’s shelf

Want to keep exploring literary criticism? I’ve curated a new Bookshop.org shop page where you can find all my recommendations and literary critic classics.

📚 Building Your Lit-Scholar Shelf

Purchasing through Bookshop supports independent bookstores — and a small portion supports Closely Reading at no extra cost to you.

🕯️ This winter, make time for deeper attention and reading

Join Closely Reading for close-reading guides, archives, and book-club discussions:

💌 $15/year: Thoughtful support

📚 $25/year: The classic close reader (Most popular!)

🪴$50/year : The sustaining member (Supports new projects!)

✨$100/year: The patron of the literary arts

Up next in the series…

Part 3 will be all about how to “reverse outline” academic articles. Make sure you’re subscribed, so you don’t miss out.

I really wish I'd been taught these skills when I was in grad school. Reading academic articles always felt like such a chore. Now I'm choosing to read them, and it's so much more enjoyable.

Confession: Ever since taking a 2-day-a-week, three hour long undergraduate night class called Lit Crit, taught by a twenty-something professor who refused to be addressed as "Dr." and assigned us, among other great works, The Yellow Wallpaper...

I have loved reading literary criticism and analyses!

This series is really great, Haley...you're building such a lovely (accessible) bridge to one of the most beneficial tools readers can use as we engage with the literary arts.

(Reminder...with a Google account, anyone (even those NOT enrolled in a uni) may register for a JSTOR account--100 free articles/month--honestly, it's really quite dangerous!). ♡