from a narrator's point of view

on the difficulties of free indirect and crafting narrators, featuring insights and lots of love for Gatsby from fiction writer Sean Crouch, MFA

Hi!

Welcome to a *~*special edition*~* of our newsletter.

I’m excited to share thoughts on the art of narration with you today. We’re currently reading Pride & Prejudice for the book club, so I’ve been all tangled up in thoughts about the powerful, unique, and deeply strange positioning of Austen’s narrator in that particular novel.

Who is that narrator? Are they omniscient? (Not purely.) Are they a fellow townsperson? (No…they have too much knowledge of others’ thoughts!) Are they a single person? (Maybe…but how can one person know so much about Darcy’s secret feelings as well as Lizzy’s private humiliations on top of the family’s general tension toward the entail and all of the stuff about universal laws and single men?)

As I’ve been closely reading our assigned chapters each week, I’ve been discussing the narrator a lot with my husband, Sean Crouch—a writer with his MFA in Fiction from beloved Oregon State University, and an absolutely lovely man who I forced to read Pride and Prejudice with me quite a few years ago. He read it; he loved it; and we still talk about it all the time. (We even regularly watch the 2005 film adaptation together—we’re both totally in love with Donald Sutherland’s interpretation of Mr. Bennet.)

Anyway.

Last week, I asked him to tell me more about the unique voice of Austen’s narrator in Pride and Prejudice — especially when it comes to what it takes to craft such an unexpected narrative voice.

I’ve broken up his brilliant thoughts as a series of answers to questions we discussed together over a long evening with our copies of the novel draped over our laps. Here’s what he had to say.

What does it take to create a narrator?

(SC) From a craft standpoint, writers need a lot of carefully planned narrative flexibility to give the reader what they need to know in order to be emotionally connected to characters and compelled by events in a story. Most of a story exists in white space, and bridging the gap between information and no information—the place where imagination takes over to create a whole world with real people—is built on two things: verisimilitude and narrative distance.

Pride and Prejudice does both, but one of the things it’s famous for is perpetuating (if not inventing) a narrative distance we call “free indirect."

So, what is “narrative distance”?

(SC) Narrative distance is the space where the narrator attaches to the point-of-view of characters. In its simplest form, we talk about first, second, and third person. But writers often come up against problems with story and emotion that require movement into less defined spaces.

Sometimes, a story is best told through first-person perspective, but the writer needs to have a moment where they can zoom out to make a scene work.

In pure first person, narrative distance is zero. The perspective is the character, with no external narrator shaping the understanding of what happens (The Great Gatsby, for example).

Pure third person is the opposite, with full access into all events, all thoughts, and while it’s a great tool for plot, it makes it difficult for the writer to attach to a single character for reasons of empathy (Harry Potter, for example).

As a note, both Gatsby and Potter have moments where the narrative distance expands or contracts. There’s no such thing as a novel without narrative flex (read the last three paragraphs of Gatsby and tell me, are you sure that’s Nick? Are you sure it’s Fitzgerald? Is it someone else?).

Most writers move between these spaces, carefully flexing narrative distance like adjusting a lens on a telescope. Perfect calibration is not too far out, not too far in. It allows the reader to see what they need to see to understand and empathize, without breaking the rules of the story.

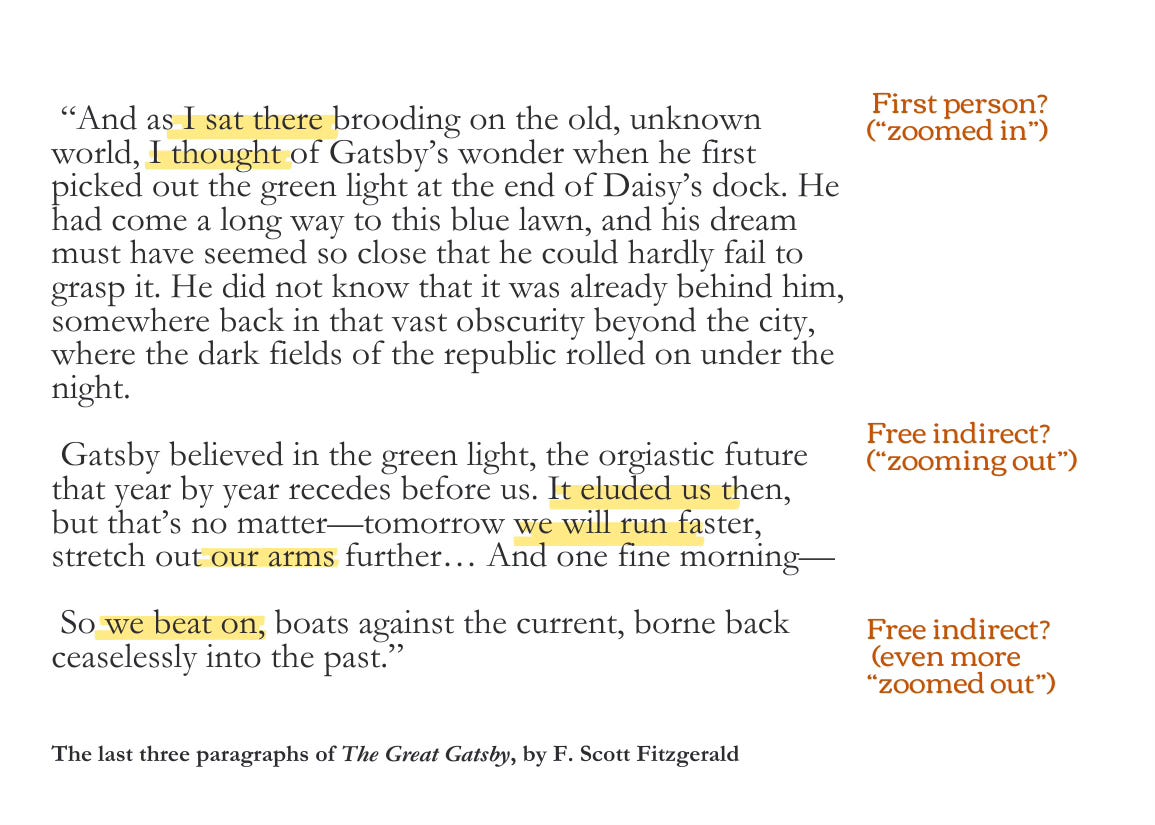

Sean and I could talk about Gatsby for days. And we have. Haha. So, here’s a rough, simple annotation of the narrative moves Sean mentions above, which happen almost perfectly sequentially in the final three paragraphs of The Great Gatsby.

Watch how Fitzgerald moves from a tight, first-person lens within Nick’s mind (“and as I sat there brooding…”) and perspective to a wider belief system and perspective (“it eluded us then,” who is “us?”), and then the widest vantage point possible (“So we beat on”—the “we” seems to have become universal, no?).

Is the final paragraph even a narrator anymore? Is it Fitzgerald, himself?

What’s “free indirect,” then, when it comes to distance?

(SC) Free indirect is the movement of that lens, in and out, to bring the ultimate sharpness to emotions and ideas when we need to be close to a character, but wide zoom when we need to understand events and ideas from others. If we were in pure first, we might not understand what’s going on around the character; if we were in pure third, we might not feel connected to the emotional weight of someone we’re seeing as a real person in a real world.

Free indirect can be difficult to recognize, for this reason. The movement, or calibration, can feel like first person in some stories, third person in others. And that’s the point. It’s “free” and it’s “indirect.” It moves as the writer—and more importantly, the characters—move to live in this real world with real people.

What makes it difficult to write “free indirect” successfully?

(SC) To build that white space, writers like Austen make moves that need to be made in order to make the story work. It’s a function of the reality of storytelling, not so much a function of authorial intention.

Austen could have written Pride and Prejudice as a third-person story, but we would have missed something of Elizebeth’s heart, her mind, her perspective on the world. More importantly, we would have missed her wit, charm, intellect, and vulnerability. That feeling would have been shifted into the narrative distance.

On the other hand, a pure first-person craft move would have cost us an understanding of the world around her, the emotional connection we have to her sisters—as us, not as Elizabeth—as well as the social construct of the time, and the wit, charm, intellect, and vulnerability of Austen’s narrator.

I like this idea of a camera lens, zooming in and out, to create or minimize distance.

(SC) When Austen zooms in, she gives us more Elizabeth, at a narrative distance that is very close to first person. It’s only inches away from being Elizabeth. We get to live her life with her.

When Austen zooms out, we understand the world around Elizabeth, and we get to see how the world affects her, and why she feels like she needs to respond and act the way she does.

A final thought

(SC) Free indirect is actually very difficult to execute, despite the fact that it sounds so flexible. In fact, its flexibility can quickly become a problem for writers.

Free indirect relies on a very precise understanding of the boundaries around a story (which we call verisimilitude).

If a writer moves the narrative distance too much from first to third, the reader detects a change in the rules of the story, and it breaks them out of the immersive spell of the world and characters. The same with moving too much from third to first.

Today, we see free indirect used often in literary fiction, so we’re comfortable with it as readers. But 200 years ago… Whether Austen was following forms that were emerging in the zeitgeist, or she was simply following her own instincts and professional honing, her execution of free indirect at a time when the form was nascent shows incredible craft control of storytelling where narrative distance and empathy are concerned.

Thank you, Sean

Our discussion has helped me do a few things—not the least of which is give Austen even more credit than I already thought was her due.

When I read the first sentence of the novel again, I wonder at the wildly ambitious craft of it. It’s a third-person statement that feels omniscient, but trembles with subjectivity, hinting at a completely un-objective stance, and making me question my first impression of the novel.

Soon after, we get moments inside Lizzy’s head—intimate knowledge of her pain and humiliation at being thought “barely tolerable” by Darcy in the dance hall. Chapters later, we’re inside Darcy’s head as he wonders at his growing affection for exactly the wrong girl and admits to feeling bewitched by her.

These are those moments that feel almost first-person, and the boundaries between “self” and “society” blur. Our narrator seamlessly guides us between fluid feelings and brilliantly rendered banter—the lack of assignations (“Darcy said, Lizzy replied”) seeming to compound these free-flowing movements as we “zoom in and out” to wherever the narrator needs us to be. This is a porous and generous world; this is a world where secrets and privacy are of the utmost importance—and are handled deftly by a narrator whose wit and charm are matched only by those timeless and inimitable characters in the pages.

How brilliant, I keep thinking, that we flow so readily with our narrator. And what depth of craft and thought and art has gone into creating that flow for us. What a gift, from Austen to us, over 200 years later, to be carried into a whole new world and guided through it with every careful adjustment of her “free and indirect lens.”

I am thinking about narration in such a deeper way now.

One of the best parts of being married to another writer is how differently we come at questions of closely reading. For him, there’s always an awareness of craft—of what it actually takes to pull of a certain literary device, technique, or style. For me, having always stayed on the reader/critic side of the line, I tend to pay a lot more attention to how well the devices, techniques, and styles serve the total system of the story.

Together, we often come to a much deeper understanding of literature and stories (and even TV shows like Severance) because we’re paying attention in different ways. We’re both “closely reading,” but how we arrive at our reading of a story—or how we form an analysis of a story—ends up being drastically different.

I invite you to wonder about how your own close reading practices might teach you about the ways you “pay attention” to stories. And, upon reflecting, I’d invite you to expand the ways you pay attention by trying new annotation styles, picking up a book in a genre you don’t typically read, or sparking a conversation about a story you love with your bookish community—whether that’s in your kitchen or here in the comments. I always love to hear your thoughts.

Cheers!

And ‘til next time, happy reading.

I'm a birder so it's second nature to me using a lens to switch between a focus on fine detail and monitoring activity in a wider environment. I feel like I've just been given a key that unlocks a completely new way of reading and experiencing story telling. It makes me want to go and reread everything I've read. I think even interacting with others in real life that I'm now going to have that idea of focus in the back of my mind. I feel a little like Dorothy in Oz just noticing color.

Great piece—thank you! So many insights and reminders for me. For instance, as a writer you do move in and out and the story can do that for you if you let it. I realize in hindsight that is what happened in the best chapters of my first novel. In my second, I am alternating first-person narratives chapter by chapter and attempting to let them zoom in on each other.

Austen is amazing. I am reading Persuasion (my first Austen) with Henry Eliot and he just talked about free indirect in his video. Strikes me so far in Persuasion that she is the antithesis of the “show-don’t-tell” school.

Severance—would love to hear you and your husband’s take on the craft/storytelling of that. Wow.