A deep dive into Passing

A literary analysis of Passing, plus a long list of recommended readings and research

Hi friends,

Welcome to a bonus follow-up from our close reading of Passing, the 1929 novel by Nella Larsen.

In today’s post, designed for paid subscribers who’d like to take a much deeper dive into the novel with me, I’m sharing about my reading and note-taking practice, including how I collect my thoughts when I know I’d like to write a more analytical piece about a novel. Then, I am sharing the first draft of my literary analysis of the novel—you’ll see it’s a bit rough, still, at this stage. Ripe for more revision in the future!

At the end, I’m also sharing a comprehensive list of related readings from academics, contemporary authors, and lit mags.

Next week, we’re diving into some spooky stories together—check out the fall syllabus for the full line-up.

(If you’re a college or graduate student, or are otherwise pressed for cash and would like access to paid content on Closely Reading, please reach out to me on the DMs here on Substack and I will upgrade your subscription for free!.)

Okay — let’s dive in.

My drafting process

Most of my research and writing steps are habitual at this point, thanks to 10+ years as a student of literature at the university and graduate level. I’ve also adopted a few quieter habits in the years since my departure from academia.

My process involves a lot of handwritten notes on loose-leaf, lined notebook paper. Sometimes I start simply, making a list of scenes I liked or remember the most, or making a few bulleted items about keywords or elements of the novel I enjoyed. I don’t always have a “center” to work from, and even when I do, I find myself leaping away from it as much as I run toward it.

When I know I’d like to do a very close reading of a specific theme or scene in the novel, I lean into keywords that struck me while reading. This a rather language-focused way of closely reading a passage, and it’s only one style of closely reading. I’m always delighted to hear how others look at a passage in a book and begin to unravel its layered meanings. For me, that unraveling happens most magically when I dig into the words themselves—their definitions, their contradictions, their repetition or lack thereof.

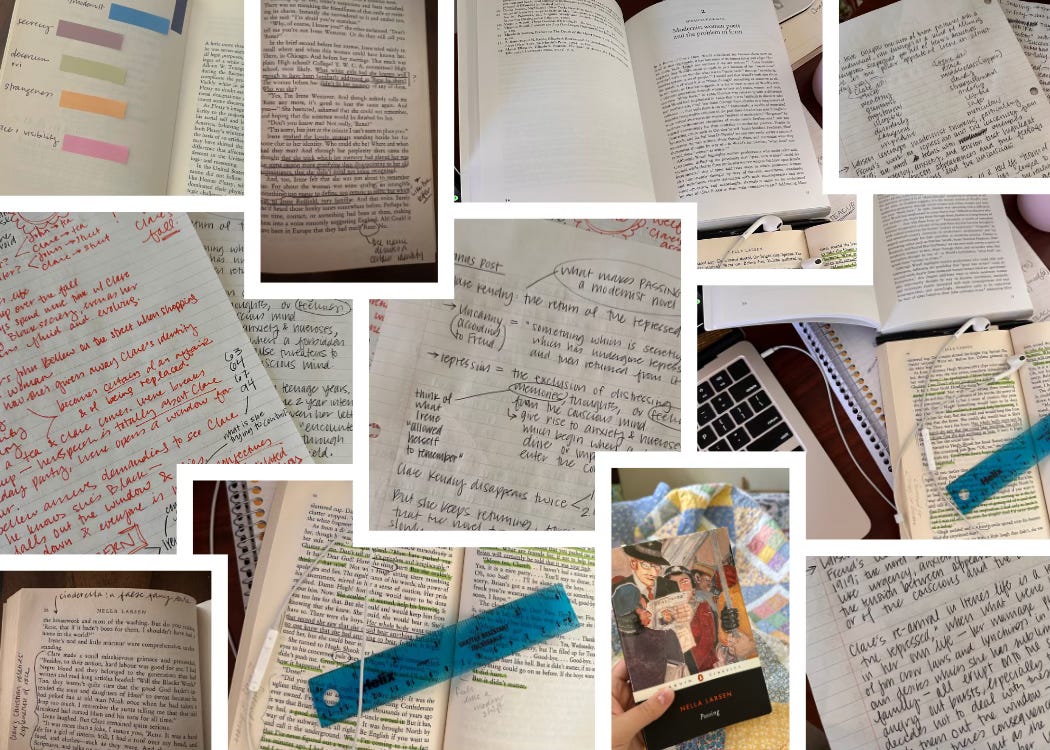

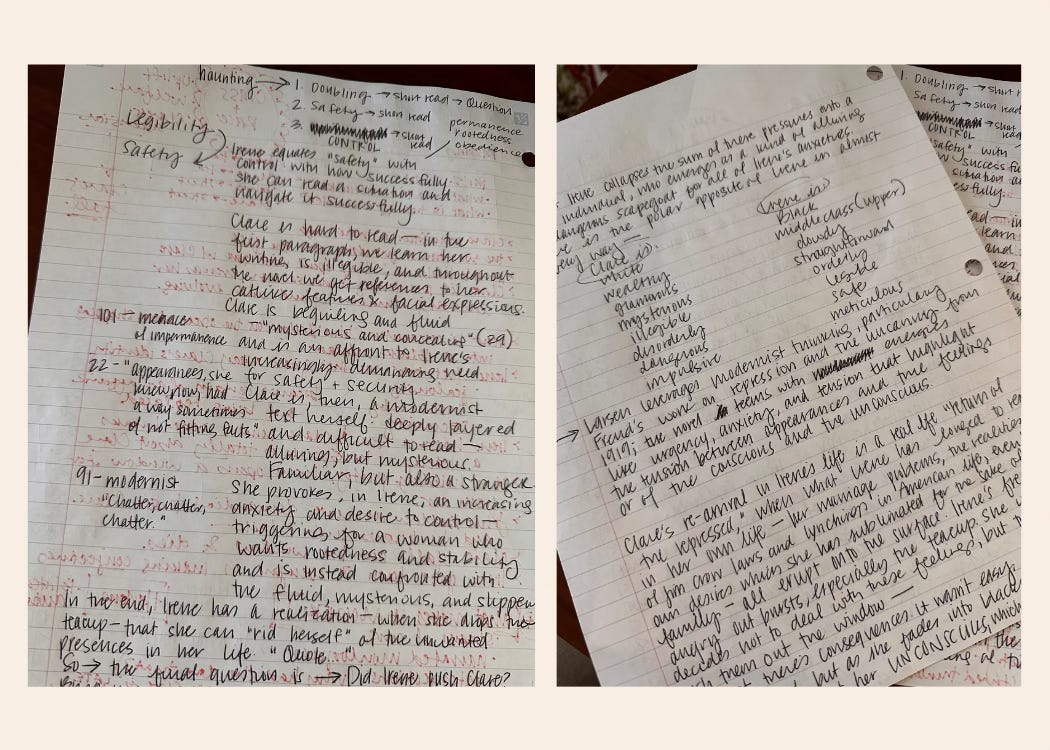

To do this, I typically list the key terms I noticed or circled while reading (see photo below: “legibility” and “safety” on the left, as well as a list of keywords about each main character on the right). Then, I give myself free association time: what other scenes did I noticed these words in? What do these words mean? What are other, similar words that do or do not appear in the text? (A dictionary and a thesaurus are especially keen tools for this exploration.)

Then, I simply let the ink flow. I doodle ideas, follow wild trains of thought, and try to capture all the little tangents that arise as I’m brainstorming. My drafting approach is, ultimately, very much a “stream of consciousness” exercise, where I am pulling ideas onto the page, fresh from my mind.

Yes: this means a lot of half-baked sentences and disjointed ideas as the bits are bouncing around in my head and sparking in fragments on the page.

Over the years, I’ve experimented with what works best for me—different kinds of paper, different pens, brainstorming in public vs. in private, writing an essay without drafting or outlining first, writing a rigid outline and forcing myself to stick to it… and I’ve realized, over and over again, that handwritten notes are where it’s at for me. This is how I figure out what I actually think about a piece of literature and how I record the “atoms as they fall,” as Virginia Woolf once said, to parse out the truth of my experience reading.

I now treasure the messy handwritten stage the most. It’s my very favorite part. There’s something about pen-on-notebook-paper that brings me into a very focused yet free state of mind—where I’m completely safe and open with myself to find out what I believe, what I think, and what I want to say.

The notes I’ve collected here showcase the rather haphazard approach I take to note-taking after reading. I don’t have a tidy system. I use arrows, as well as page numbers and quotes, in lots of different ways, all over the paper. I also get really bothered when I misspell something or a letter comes out wonky, so I will cross it out and rewrite it. Lots of scribbles.

The result is a messy little mind map, a reflection of the true energetic frenzy taking place up there in my brain after I finish reading something as good as this book.

Once I have a pile of pages, I know I’m ready to shift from doodling notes to writing fuller thoughts out on the screen. Whenever I get stuck digitally, I come back to paper and keep the ink running until I figure out my next move. I used the pages pictured in the images above to help me write today’s essay.

Closely reading Passing

In what follows, I’m sharing a short literary analysis of the novel, written in a straightforward academic style (not the typical voice I employ, yet a quite fun one to bust out periodically, for moments such as these).

At the broadest level, I’m writing this essay to help me (and perhaps you) better understand that particular brand of fear experienced by Irene Redfield throughout the novel and how, so heightened in her anxieties, she may make the final, fatal decision to push Clare Kendry out the window.

This essay explores:

How Freud’s theory of the uncanny can help us understand the tension of the novel and what is at stake for Irene in a deeper way.

How staring heightens the tension of the novel.

How Larsen leverages the language of the uncanny, through the language of staring, to compound Irene’s repressive mental state and to, in the end, show the damning power of the return of whatever has been repressed to frighten her into existential rumination.

Read on for the essay.

The return of the repressed

In 1919, Sigmund Freud penned an essay entitled, Das Unheimlich or The Uncanny, in which he analyzes the “realm of the frightening”—or what scares people, generally—and zeroes in on particular piece of it, which he calls the “uncanny.” He defines the uncanny dozens of ways throughout the essay, weaving across and throughout different cultures and languages which have language for this particular brand of fear, this zip code in the realm of what keeps us up at night.

One of his most salient descriptions of the uncanny emerges as he considers the power of the uncanny to unseat previously held positions of certainty. For Freud, the uncanny is:

“Something which is secretly familiar which has undergone repression and then returned from it.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Closely Reading to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.